By Robert Tate, Automotive Historian and Researcher

Images courtesy of the National Automotive History Collection

Posted: 11.03.2015

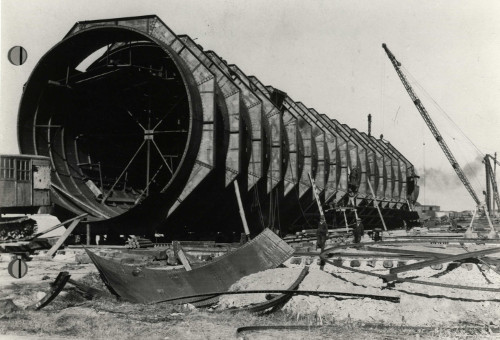

A look at early construction of one the nine connecting tubes that make up the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel.The story of the iconic Detroit-Windsor tunnel goes back nearly a decade when construction first started in the 1920s.

A look at early construction of one the nine connecting tubes that make up the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel.The story of the iconic Detroit-Windsor tunnel goes back nearly a decade when construction first started in the 1920s.

It was Edward Blake Winter, mayor of Windsor from 1919-1920, who had approached many of Detroit's politicians at the time with an idea about constructing an automobile tunnel to connect Detroit with their trans-international neighbors.

At the time, automobile sales were rising and families were traveling more and more which inspired some local leaders, including Detroit Mayor James Couzens, to support Winter’s idea for the tunnel.

After Couzens approved the initial proposal, the working relationship between the two countries was formed when Winter asked the Canadian government to subsidize construction of the tunnel. Financial support from the U.S. side came from a group of Detroit bankers who all agreed to help fund the project.

Fred Martin, who was named vice president of the company in charge of the Detroit River subway project, became one of the biggest promoters of the proposed tunnel. Martin was also responsible for securing the necessary funding needed to begin this historic tunnel connection.

Construction for the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel began in the summer of 1928 taking 26 months and a budget of $24 million to complete. Construction was completed about one year ahead of schedule.

Considered one of the greatest engineering wonders in the world, the chosen architectural firm was New York-based Parsons, Klapp Brinckerhoff and Douglas – the same company responsible for New York Subway lines.

Many to this day talk about the construction of the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel as an integral part of Detroit’s great history. Looking back at the early days of construction, there were other transportation-related projects happening locally including the construction of a railway system tunnel connecting Windsor and Detroit that had begun in 1871. That project was abandoned when some of the workers became ill and unfortunately died from gas fumes.

Tunneling under the Detroit River

When the Detroit-Windsor project began in 1928, it is said three important construction features emerged as part of the Windsor Tunnel immersed tube sections. These unique and modern construction techniques were called: Cut and Cover, Shield and Trench and Tubing.

Construction started with two tunneling shields – huge, hollow cylinders used to protect workers – that were installed with one on the U.S. side and another on the Canadian side. Then workers used a steam-powered shovel to scoop out a trench across the bottom of the Detroit River, this was called Trench and Tube.

During this process, the mud from excavation was taken away by work boats called “Scows.”

On the Canadian side, shore workers constructed nine steel cylinders reinforced with steel plates that were welded together to create watertight tubes.

The tubes were strengthened on the outside with eight-sided support rings and inside rings. Later, temporary wooden bulkheads were placed at each end which were supported by steel trusses inside and covered outside by one-inch steel sheeting and seven-ply waterproofing.

Workers had created manholes to complete the job with the roadbed and concrete work that followed. Some of the construction workers were called “Muckers or sand hogs as their job was to manually cut the earth away using nothing but hand tools to cut a path for a giant shield wall.

To position the reinforced tubes, tugboats positioned each cylinder directly over the trench area, where the tubes were pumped full of water and sunk to the bottom starting on the American side of the river.

Nine sections in all were sunk and placed in the trench area. An experienced diver secured the sections with large steel pins. Then all of the sections were covered in special underwater setting concrete, but the most important task was to join and connect the various parts of the tunnel together.

The tunnel sections have three main levels: The bottom level brings in fresh air under pressure, which is forced into the mid-level where the traffic lanes are located. A ventilation section was built at each end of the tunnel. Each section was given 12 fans – six to draw in fresh air and six to blow out used air and automobile emissions. The air inside the tunnel completely changes every 90 seconds.

On a historical note, because the tunnel essentially sits on the river bottom, there is a wide no-anchor zone enforced on all river traffic.

After many months of complex construction, the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel was completed in 1930. The two-lane roadway is 75 feet below the river surface which is amazing for traveling to another country.

Vehicles pay a fee to pass through the tunnel, motorcycles are prohibited from using the tunnel. For more than 80 years the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel is still regarded as one of the great engineering wonders of the world and will always be a part of Detroit's great heritage.

A special thanks to Robert Tate, Automotive Historian and Researcher, for contributing the story to the MotorCities Story of the Week program. Photographs are courtesy of Robert Tate's personal collection. (Bibliography: Mc Call M.P Walter. “80 Years Of Cadillac La Salle,” Crestline Publishing 1988; Hendry D. Maurice/Editors of Automobile Quarterly “Cadillac standard of the world The Complete history,” 1979; Williams, Jim. “Boulevard Photographic The art of automobile advertising,” 1997 )

For further information on photos please visit http://www.detroitpubliclibrary.org/ or email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Please do not republish the story and/or photographs without permission of MotorCities National Heritage Area.

If you would like to contribute an article for the MotorCities newsletter, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or call 313-259-3425.