Below are downloadable lessons which would be great to use in the classroom as well as helpful links.

1910s

-

1913 Ford's Moving Assembly Line

Henry Ford realized he could sell more automobiles by producing them more efficiently. He developed a system of production that involved a moving assembly line on a conveyor belt around the building. On this assembly line, workers did not move to the automobiles; the automobiles came to them...

-

1914 William Perry is the first salaried employee

William Perry, the first known African American to work for Ford, started working at the Highland Park Plant in 1914. In the winter of 1888, Perry and Ford worked together, sharing a two-man saw on his timberland estate...

-

1914 Five Dollars a Day

The work environment on the assembly line at Ford was tedious, repetitive and tiring. Because of these conditions, many employees did not last long at Ford. In order to slow the turnover rate, Ford introduced job incentives to his employees...

-

1915 The Great Migration Begins

Southern life in 1915 was difficult for many African Americans because of racial discrimination and crop failures caused by a Boll Weevil infestation. African American sharecroppers were out of work and had no other options in the south...

-

1916 The Detroit Urban League Formed

Forrester B. Washington and Henry G. Stevens opened the first Detroit Urban League office in 1916. John C. Dancy was appointed executive director after Washington and served for 42 years...

-

1917 World War I Begins

The Great War, later named World War I, had been well under way in Europe since 1914, before the United States became involved on April 6th, 1917. Conflicts began with the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which caused tensions between Austro-Hungary and Serbia...

-

1917 Ford's River Rouge Plant Opens

In 1917, Henry Ford purchased marshland in Dearborn, Michigan near the Rouge River for the site of the new Rouge plant. Architect Albert Kahn agreed to design the Rouge plant and the Eagle Boat Factory on the project site...

-

1919 African American Education

African American children who resided in the Metro Detroit area attended Wingert Elementary School. In the next three years they would come to represent a third of the school's population...

1920s

-

1920 Dodge Employs African Americans

By 1920 many auto companies, with the exclusion of Henry Ford, still did not employ African Americans. John Dancy, the president of the Urban League, went to John Dodge and asked him to hire African Americans...

-

1922 The Graystone Ballroom Opened

In the 1920's ballrooms were a very popular form of recreation for young people in the city. As Paradise Valley emerged near Black Bottom, ballrooms became a very common place for people to go to during leisure times, where they could dance and listen to music...

-

1924 African American Professionals

In 1924, there were 80,000 African Americans living in the city of Detroit, double the population four years before. Groups like the Detroit Urban League worked hard to find jobs, housing and medical assistance for the newcomers...

-

1926 The 40-Hour Workweek

Ford believed that a worker should be allowed leisure time just like the salaried employee above him. He argued time off was not time wasted because it encouraged the workers to do a better job when on the clock...

-

1929 The Ambassador Bridge Opens

The commencement ceremony was held for the Ambassador Bridge on November 11th. Large crowds of 50,000 gathered on the Canadian side and possibly up to 100,000 on the American side. Sirens were sounded from factories and a plane dropped balloons over the center of the bridge...

-

1929 Ford Employs African American Tradesmen and Management

One of the first automobile companies to hire African Americans and the first to offer an equal wage, Ford Motor Company continued to be one of the largest employers of African Americans...

-

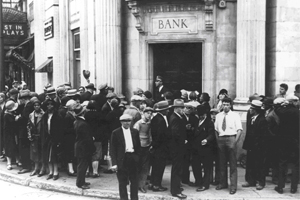

1929 The Great Depression

In 1929, 15 million Americans were out of the workforce and 45 million were unemployed. Approximately 60 percent of blacks were unemployed and had to seek welfare assistance in order to survive...

1930s

-

1932 The Ford Hunger March

The Ford Hunger March, also known as the Battle at River Rouge took place on March 7 at the Ford Motor Company River Rouge Plant. 75 percent of the workforce at this plant had been laid off and without public relief people were dying of cold and hunger...

-

1933 Second Baptist Church Raises Half a Million Dollars

Second Baptist Church, between 1914 and 1933, raised and spent more than half a million dollars in serving the black community in Detroit. Founded in 1836, Second Baptist Church was and still is an active force...

-

1935 United Auto Workers Formed

August 26, 1935, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) officially chartered the United Auto Workers (UAW) in Detroit, Michigan. Francis Dillon was its first president. The UAW was among one of few labor unions to organize African Americans...

-

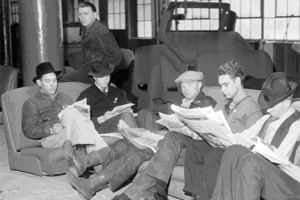

1936 The Flint Sit-Down Strike

The 1936 Flint Sit-Down strike took the UAW from a collection of isolated locals on the outside of the industry to a major union that led to the unionization of the domestic auto industry...

-

1937 The Battle of the Overpass

On May 26, 1937, union organizers clashed with Ford Motor Company's Service Department; an internal security force under the direction of Harry Bennett. The UAW planned a leaflet campaign entitled, "Unionism, Not Fordism,"...

-

1939 Davis Motor Sales Opens

At 16 years of age, Edward Davis began his career in Detroit's auto industry working first at a car garage and then a small car washing business. After graduating high school, he worked at Dodge, first in the foundry, and soon after in the machine...

-

1939 World War II Begins

World War II (WWII) began on September 1, 1939 when German forces invaded Poland. Adolf Hitler's 'Blitzkrieg', or 'lighting war', consisted of unwarned air attacks that destroyed most of the Polish air force, bombing road, and rail...

-

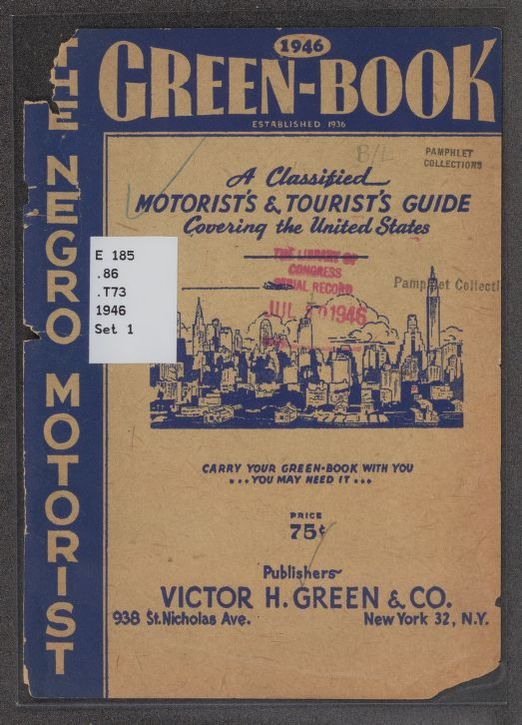

The Negro Motorist Green Book (1936-1966)

It is in the context of public transportation (on buses, streetcars, and trains) that American Blacks were exposed to some of the most brutal forms of racial discrimination from the late nineteenth century through the civil rights movement. In the South, the Jim Crow laws were applied in seating arrangements, waiting rooms and bathrooms, for drinking fountains, etc. Thus, the automobile represented, in the eyes of many African Americans who could afford one, the possibility to break out of the constraints and humiliation of Jim Crow laws. However, traveling by car still represented very serious challenges for American Blacks, who often couldn’t use the bathrooms or restaurants at roadside service stations, for example – while these arrangements were supported by the Jim Crow laws in the South, they also existed elsewhere in the United States. Mia Bay writes: “[…] black drivers learned to assemble Jim Crow kits before driving any distance. They loaded up their cars with food, water, and maps (so they would not have to stop and ask for directions) and carried amenities such as toilet paper and “pee cans,” assuming that they would not be able to use roadside restaurants. Many also filled their gas tanks before leaving home and even carried additional gas in the trunks of their cars. If they had to stop for gas, they tried to time their trips so they could make such stops in major cities.”

Green Book cover page courtesy of Library of Congress

The necessity of carefully planning one’s trip as an African American motorist is an element on which the early editions of The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide founded by Victor Green in 1936, insisted, focusing for instance on the importance of maintaining one’s car in good condition “to avoid mechanical problems on the road that could leave riders stranded and in a dangerous predicament”. The first issue of the Green Book was published in 1937 by Green and his partner George L. Smith. After Smith’s death, Victor Green secured the collaboration of his brother William, who remained on board until 1945. When Victor retired in 1952, his wife Alma took over the role of publisher while Victor remained her adviser. The Green Book’s goal was to create a geographically organized list of community services and businesses that were welcoming of African Americans, in order to inform them where they would be received, and where they wouldn’t be – which was most helpful for African Americans on the road. Most of the businesses featured in The Green Book were owned by African Americans, but the guide also included advertisements from welcoming white-owned businesses. Initially, the Green Book focused on the New York city area, but it expanded over time, emphasizing major cities in the East, including Cincinnati, Washington, DC, and Baltimore. By the mid-1960s, the book included listings all over America – though states were of course not equally represented: “The Green Book identified relatively few accommodations in South Dakota and Wyoming, which had tiny black populations,” writes Gretchen Sorin. Travel tips, listings of hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, doctors’ offices, drugstores, beauty parlors, barbershops, taverns, and service stations welcoming of black customers, and advertisements for some of the businesses it mentioned were all included in the Green Book. Victor Green’s guide was meant to be appealing to a wide audience across social classes, since it encompassed a variety of establishments: in lodging, for example, he included affordable rooms in YMCAs and various types of accommodations up to hotels.

Gretchen Sorin mentions that Victor Green identified guides written for Jewish travelers as the inspiration for his own, while Mia Bay mentions an additional source of inspiration, the Automobile Green Book, a road guide to the East Coast published by the Automobile Legal Association. A lot of the information contained in the Green Book came from its readers and their own travel experiences as customers, but Green also paid travel agents for their contributions; additionally, the publisher sent out annual letters and postcards encouraging business owners to purchase advertisements in the guide.

Victor Hugo Green in 1956

Most editions of the Green Book contained articles, but these were rather short at the beginning of the guide’s existence; throughout the years, though, the guide integrated more expansive articles, portraying, for example, “cities with large and welcoming black neighborhoods, like Chicago and Louisville, that catered to tourists.” The listings and advertisements, however, remained at the very heart of the Green Book’s mission.

Standard Oil Company became the privileged business partner of Victor Green; indeed, its Esso gas stations sold The Green Book starting in the mid-1940s or offered it as a promotional item to customers. The United States Travel Bureau also endorsed the guide, which gave the book national attention. Other partnerships developed by Green to foster the book’s distribution included several travel clubs and bureaus, automobile clubs, the armed forces, bookstores, bus and airline companies, and the Idlewild Chamber of Commerce – a large African American resort in Michigan.

By the beginning of the 1950s, The Green Book included listings for lodgings in Canada and Mexico, the Caribbean, Costa Rica, Bermuda and the Virgin Islands; later, by the 1960s, the guide included listings for Europe and Africa. Interestingly, while commentators like Gretchen Sorin mention that the Green Book was at first reserved in its tone regarding racial issues, since Green and his team knew that they relied heavily on white allies, corporations and government agencies to ensure the survival of their publication, Sorin also insists on the fact that the Green Books of the 1960s explicitly supported the civil rights movement:

“In a feature entitled "Your Rights, Briefly Speaking," drawn from a list compiled by the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, Green Book writers listed the states that passed laws against any form of discrimination. […] this segment sought to inspire readers to challenge the laws by reporting violations experienced during travel to the appropriate human rights commission. Contact information was included for each of the 20 states with such commissions. The descriptions of the violations encouraged readers to file lawsuits, to seek monetary damages against wrongful actions, and to demonstrate peacefully.”

Other travel guides were created in the attempt to help black drivers overcome some of the difficulties they faced on the road. Other than the Green Book, other guides included Hackley and Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers (1930-1931); The Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring (1952-1959); and Travelguide (1947-1963). The Green Book, however, was the longest lasting – published from 1937 to 1966. It was also the most widely distributed of these guides, reaching a circulation of 2 million in 1962.

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

-Bay, Mia, “Traveling Black/Buying Black. Retail and Roadside Accommodations during the Segregation Era,” in Ann Fabian and Mia Bay (eds.), Race and Retail: Consumption across the Color Line, New Brunswick (N.J.), Rutgers University Press, 2015, p. 15-33.

-Sorin, Gretchen, “Victor and Alma Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book,” in

Driving While Black. African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights, New York, Liveright Publishing Corporation (a division of W. W. Norton & Company), 2020, p. 176-214.

-Sugrue, Thomas J., “Driving While Black: The Car and Race Relations in Modern America.” Automobile in American Life and Society, Science and Technology Studies Program at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and Benson Ford Research Center (The Henry Ford), 2004-2010, http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Race/R_Casestudy/R_Casestudy1.htm

- Mia Bay, “Traveling Black/Buying Black. Retail and Roadside Accommodations during the Segregation Era,” in Ann Fabian and Mia Bay (eds.), Race and Retail: Consumption across the Color Line, New Brunswick (N.J.), Rutgers University Press, 2015, p. 23.

- Gretchen Sorin, “Victor and Alma Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book,” in Driving While Black. African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights, New York, Liveright Publishing Corporation (a division of W. W. Norton & Company), 2020, p. 195.

- I owe this “genesis” of Green’s publication to Gretchen Sorin (Ibid., p. 182).

- Ibid., p. 204.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 181.

- Ibid., p. 184.

- Mia Bay, op. cit., p. 25.

- Gretchen Sorin, op. cit., p. 200-204.

- Ibid., p. 196.

- Ibid., p. 193-194.

- Ibid., p. 209.

- Ibid., p. 211-212.

- Mia Bay, op. cit., p. 24.

1940s

-

1941 The River Rouge Sit-Down Strike

In April 1941, Ford remained the last major auto company that refused to recognize unions. When eight Ford employees were fired for joining the UAW, the entire labor force walked out on strike...

-

1942 War Production Began

Car production in the United States came to a halt when America entered World War II. Ford Motor Company began building B-24 bombers and other war armaments on their assembly lines...

-

1943 The Packard Motor Company Strike

Although Packard Motor Company employed African Americans the plant was segregated and restricted black workers to the foundry or sanitation. In 1941 racial tensions became violent when Packard promoted black...

-

1944 Women in the Auto Industry

The United States' decision to enter World War II in 1941, created a labor shortage as hundreds of thousands of men were sent off to war. Jobs were again open to women for the first time since World War I...

-

End of Segregation in Armed Services

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981: Desegregation of the Armed Forces, establishing the Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services and ordering full integration of all the services. Executive Order 9981 specifically stated that “there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.”

The order also implied the creation of an advisory committee charged with examining the practices of the Armed Services and to recommend strategies to concretely achieve desegregation. In his book Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940-1965, Morris J. MacGregor, Jr. explained how essential the civil rights movement was on the integration of the Armed Services. The civil rights advocates traded their political support for equality opportunity reforms in a number of elections: their impact was crucial in Roosevelt’s decision to recruit Blacks for general service in the World War II Navy and all branches of the Army, for example, and in Truman’s Executive Order 9981. MacGregor also recalled that resistance to reform was found in the military, notably from so-called military traditionalists whose defense of military tradition often hid bigotry. Traditionalists argued that black servicemen were unreliable in battle, but also that the military’s purpose was not to be a catalyst for social change.

However, as we know, the integration of the military in the 1950s was a success and undermined the traditionalists’ concerns. In particular, individual black servicemen performed well in integrated units, revealing that new social and interactional dynamics could also lead to improved well-being and achievements. Some commanders who, contrary to expectations, began to fight in the Korean War with segregated units, realized that their black servicemen performed better when they began integrating their forces. Accounts of the treatment of the 24th Infantry in the Korean War also revealed the systemic racism faced by the remaining all-black regiment in the conflict obstacles faced in training by African American soldiers at war were also due to segregationist education policies, that is, their unequal educational background in comparison to that of their white peers.

The effective integration of all active military units dates from 1954. The Navy is considered a pioneer in terms of integration, as it created a policy of integration as soon as February 1946. In a number of ways, the successful integration of the armed services put them at the forefront in the nation’s struggle for racial equality: “By demonstrating that large numbers of blacks and whites could work and live together, they destroyed a fundamental argument of the opponents of integration and made further reforms possible if not imperative.”

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Executive Order 9981, July 26, 1948; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

“Executive Order 9981: Desegregation of the Armed Forces (1948).” Our Documents. A National Initiative on American History, Civics, and Service, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=84 . Accessed 14 January 2022.

Morris J. MacGregor, Jr. Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940-1965. Washington, D.C., Center of Military History (U.S. Army), 1981, p. 609-610.

“Fighting Together in Korea.” BBC World Service – The Documentary Podcast, 24 October 2020, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/w3ct16c6 .

[1] James A. Geschwender, Class, Race, and Worker Insurgency. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 88-89.