By David Elsila, Michigan Labor History Society

Posted 04.18.2017

The GM-Ternstedt Factory circa 1937.In the spring of 1937, workers at the huge General Motors Ternstedt plant in the Livernois-Fort neighborhood of Detroit faced a dilemma.

The GM-Ternstedt Factory circa 1937.In the spring of 1937, workers at the huge General Motors Ternstedt plant in the Livernois-Fort neighborhood of Detroit faced a dilemma.

The workers were demanding a contract, including recognition, fair wages, and an end to favoritism, but were getting nowhere in their negotiations with management. The national agreement between the UAW and General Motors, reached a couple of months earlier following the Flint sit-down strike, barred them or any GM workers from striking. How could Ternstedt workers pressure management without the right to strike?

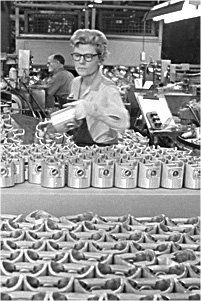

Ternstedt was the largest GM plant in Detroit. It had 12,000 workers, the overwhelming majority of them women, who made door handles and other chromium parts for GM vehicles. The company had hired mostly women workers because it felt women could manipulate small parts more easily than men.

Stanley Nowak, then a UAW organizer and later a Michigan state senator for 10 years, recalled how women at Ternstedt faced sexual harassment and discrimination. According to Nowak, the women complained that male supervisors demanded dates in exchange for desirable jobs.

Nowak also spoke about managers pitting ethnic groups against one another. When southern transplants complained that they weren’t getting a promised productivity bonus, managers reportedly would respond that the Polish workers had produced so much that they’d been the one to receive the bonuses. But when asked by the Polish workers where their bonuses were, the managers would turn tables and say the southerners had received them.

Into this situation came the UAW fresh from its victory in Flint. Although some organizers didn’t think they could attract women workers into the union, Nowak, an organizer for West Side Local 174, disagreed. “I have found women very dependable, vocal, and militant,” Nowak said, “often more so than men.”

Nowak led a union bargaining committee with a large group of women to meet with S.E. Skinner, the Ternstedt manager. Skinner met with the union for weeks but would make no concessions. Although frustrated by his stalling, UAW leaders were reluctant to take any overt action that might jeopardize the new national agreement with GM.

A woman from the GM-Ternstedt Factory working on parts in 1937.But Nowak came up with a solution to the dilemma. He recalled a conversation in Chicago with an old European-born worker whose union had faced a similar problem in Vienna. Instead of striking, the Vienna workers had acted together to deliberately cut their productivity – a “slowdown.” The worker had given Nowak a book describing the tactic, and Nowak went home to read it.

A woman from the GM-Ternstedt Factory working on parts in 1937.But Nowak came up with a solution to the dilemma. He recalled a conversation in Chicago with an old European-born worker whose union had faced a similar problem in Vienna. Instead of striking, the Vienna workers had acted together to deliberately cut their productivity – a “slowdown.” The worker had given Nowak a book describing the tactic, and Nowak went home to read it.

Leaders of the growing Ternstedt UAW group began to discuss the idea of conducting their own “slowdown.” Word was passed quietly to union stewards and then to trusted rank-and-file workers. On the same day that UAW bargainers next met with Skinner, workers started a rolling slowdown, department by department, maintaining some production but cutting it by up to 50 percent.

As the union once again laid out its demands at the bargaining table, Skinner was interrupted by several phone calls. Nowak recalls that he became increasingly agitated. Apparently Skinner was getting reports from several shop-floor supervisors of the production slowdown. Looking up from the phone, Skinner yelled, “you sonofabitch,” at the union organizer, and he ordered the entire union team to leave.

The slowdown tactic worked. Within days, Skinner contacted the union to come back to meet with him. The company agreed to recognize the union at the plant, abolished piecework, and eventually negotiated a day rate for pay.

The legacy of the Ternstendt slowdown lives on. Workers in other parts of the U.S. have used a “work to rule” strategy from time to time to win their demands. From Vienna to Detroit and elsewhere, labor has found creative ways to win.

(For futher information: Two Who Were There by Margaret Collingwood Nowak, Wayne State University press, and Women, Work, and Protest: A Century of U.S. Women’s Labor History, edited by Ruth Milkman, Routledge Press.)