When people hear the word “car” today, they most likely think of the automobile. But in the late 19th century, freight trains were at the heart of the American economy and one of the nation’s largest frieght car manufacturers was located in what became southwest Detroit. The skills and technological improvements in railroad car production contributed to the emerging automobile industry in the 20th century.

In 1864, during the Civil War, James McMillan and John S. Newberry started the Michigan Car Company with a $20,000 investment (the equivalent of $420,000 today). By 1873, they developed the plant complex at the intersection of the Michigan Central and the Grand Trunk railroads, that sprawled over 30 acres in Springwells, just west of what were then the Detroit city limits. Michigan Car Company’s first rail cars were made of wood, but eventually steel construction became state-of-the-art. By the end of the 19th century, production of freight cars—the gondolas, tank cars, flat cars, and hoppers that moved the nation’s grain, oil, ore, and timber--had emerged as Detroit’s most important manufacturing industry.

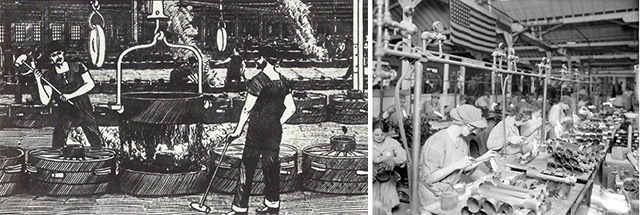

Michigan Car Company and its subsidiaries employed hundreds of Detroiters. At one point in the mid-1870s the company employed 881 production workers--566 directly by Michigan Car, and 315 by its on-site subsidiary, the Detroit Car Wheel Company--in addition to 124 clerical employees. The wheel shop could melt an average of 55 tons of iron per day to make 200 car wheels, each one 33 inches in diameter and weighing 570 pounds. This production required skilled molders and their assistants to do the dangerous job of pouring molten metal into wheel-shaped molds. After the metal cooled, they removed the rough versions of the wheels, called castings, and sent them to the machine shop for finishing. There the wheels were fitted together with axles made by the Baugh Steam Forge Company, another Michigan Car Company subsidiary. Freight cars were complicated, requiring all sorts of metal parts like straps and rods. Much of that work took place in the blacksmith shop, where sixteen-year-old Henry Ford was employed briefly in 1879. A paint shop rounded out the operations at the Springwells site.

Michigan Car Company (1885)

Michigan Car Company (1885)

The nation’s economy was volatile in the late 19th century, and the Michigan Car Company alternated between times of prosperity and economic difficulties. In the early 1880s, the company earned hefty profits of $6 million a year (roughly $170 million today), but by mid-decade hard times hit. Michigan Car Company workers who were still on the job in 1886 took center stage in an unsuccessful citywide campaign to establish the eight-hour workday. As the economy rebounded, so did Michigan Car Company, which by 1887 was one of the largest railroad car shops in the country. Its 2,500 workers could produce 10,000 cars and 110,000 car wheels a year--wheels wore out and had to be replaced--all of which required 60,000 tons of iron and 50 million feet of lumber.

Michigan Car Company continued to grow. By the early 1890s, it ultimately employed 3,000 to 4,000 workers in firms that it owned either outright or in part. Among them were:

- Detroit Steel and Spring Works, whose steel springs allowed rail cars to handle heavy loads

- Griffin Car Wheel Company, which boosted daily wheel production by 300

- Detroit Iron Furnace Company, whose Hamtramck-built furnaces melted the metal in the Springwells foundries

- Fulton Iron and Engine Works, whose downtown Detroit factory manufactured a variety of railroad-car parts

- Detroit Pipe and Foundry Co., which produced cast iron pipe for construction and water systems.

- Michigan Forge & Iron Co (originally established as Baugh Steam Forge Co), whose consisted of a rolling mill and steam forges that made axles for the Michigan Car Company

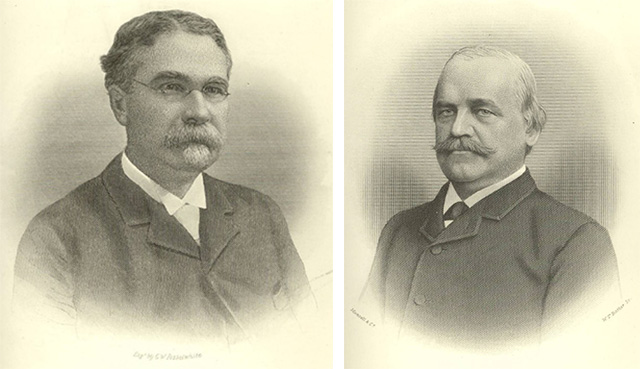

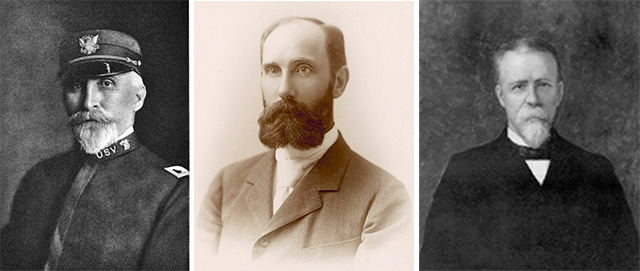

In 1892, Michigan Car Company merged with the Peninsular Car Company, a competing rail car manufacturer on the east side of Detroit, to form the Michigan-Peninsular Car Company. Owned by Colonel Frank J. Hecker, Charles L. Freer, and Russell A. Alger, Peninsular had made its mark on the industry by producing the early refrigerated cars developed by the Chicago meatpackers, Swift and Company. With the merger, the Michigan-Peninsular workforce of 5,000 turned out a total of 100 freight cars per day.

James McMillan and John S. Newberry (Michigan Car Co. – Top row) Colonel Frank J. Hecker, Charles L. Freer, and Russell A. Alger (Peninsular Car Co. – Bottom row)

James McMillan and John S. Newberry (Michigan Car Co. – Top row) Colonel Frank J. Hecker, Charles L. Freer, and Russell A. Alger (Peninsular Car Co. – Bottom row)

Then hard times returned. The national economic crash of 1893 forced Michigan-Peninsular to shut down for five months and lay off 1,200 workers. Orders for freight cars dried up as more than seventy railroad companies, including the Union Pacific, went bankrupt. Michigan-Peninsular’s earnings fell from $867,000 in 1892 to $36,000 in 1894, but the firm rebounded by 1897, when it built 44,000 units.

In 1899, Michigan-Peninsular merged with a dozen other companies across the country to form American Car & Foundry, which aimed to eliminate competition by monopolizing railcar production. The Detroit operations of American Car & Foundry represented the largest unit in the new company, manufacturing about one-third of the company’s output of 124,000 freight cars in 1899. By 1900, American Car & Foundry employed 9,000 Detroiters, about 7% of the city’s industrial workforce, and business remained strong as the company’s production reached 163,000 cars in 1902.

One reason for the dramatic increase in output in 1902 was an experimental production system, introduced in Detroit, in which trucks moved rail cars under construction from one station to another. Specialized crews at each location performed specific tasks before the car moved along to the next stage. This incorporated the concept of the moving assembly line, something that Henry Ford would take to new levels with auto production in the following decade.

Much changed in the years after the merger that created American Car & Foundry. The men who founded Michigan Car Company no longer played an active role in the business, and the merged company set up headquarters in St. Louis. The production facilities on the Springwells site assisted the nation’s efforts in World War I, with some of the facilities converted to munitions production. Near war’s end, some of the complex was converted to motor coach manufacturing. After the war, the site and its munitions plant, were cleared to make way for the new Cadillac automobile production facility.

Detroit Car & Wheel Foundry Casting Operation (1889) / AC&F Munitions Workers (1918)

Detroit Car & Wheel Foundry Casting Operation (1889) / AC&F Munitions Workers (1918)

Click to view:

Michigan – Peninsular Car Company Profile from Haye’s Hendricks’ Rolling Stock website hosted by the Mid-Continent Railway Museum. Additional detail about the careers of rail manufacturers McMillan, Newbery, Hecker, and Freer is found in the “Cast of Characters” section at the end of this post.

The Legacy of Charles L. Freer, an article by George Bulanda for Hour Detroit magazine. After withdrawing from the affairs of ACF, Charles Freer dedicated himself to collecting art. This article details Freer’s contributions to the forerunner of the Detroit Institute of Arts and to the collection that bears his name at the Smithsonian Institution.

Fighting for the Eight-Hour Day, a Michigan Labor History Society newsletter feature about the 1886 campaign for the 8 Hour Day, in which rail-car companies figured prominently.

TEXT - RON ALPERN, DIANNE FEELEY, & DANIEL CLARK

RESEARCH – DR. THOMAS KLUG’S SCHOLARHIP WAS AT THE HEART OF THIS NARRATIVE