A STORY OF THE WEEK EXTRA

by Bob Sadler, MotorCities Communications Manager

Images from Walter Reuther Library, Motown Records

Published 1.14.2022

EDITOR”S NOTE: In honor of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday, MotorCities is sharing this story of the 1963 March to Freedom event in Detroit and the role played by UAW President Walter Reuther and area auto workers.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Marches Down Woodward; Walter Reuther is on the left and Reverend C.L. Franklin on the right in the hat next to King (Reuther Library, WSU)

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Marches Down Woodward; Walter Reuther is on the left and Reverend C.L. Franklin on the right in the hat next to King (Reuther Library, WSU)

On June 23, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, along with numerous Detroit church leaders, Mayor Jerome Cavanagh and UAW President Walter Reuther, led a march down Woodward Avenue to protest unequal treatment of Black people both around the country and in Detroit. Police estimates placed the crowd that marched between 125,000 and 200,000, making it the largest civil rights demonstration in the United States at that time.

The march culminated with a program of speakers and musical performances at Cobo Arena, where over 20,000 people, along with many others gathered outside listening to loud speakers, heard King present remarks that foreshadowed his famous “I Have a Dream” speech delivered in Washington D.C. two months later.

The Detroit event came about as a response to King’s call for financial assistance for his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) ,to pay bonds, legal fees and other expenses in support of young African Americans arrested for protesting in southern cities like Birmingham, Alabama.

King’s key ally in Detroit was the Reverend C.L. Franklin, pastor of New Bethel Baptist Church and father to a 21-year-old singer named Aretha. Franklin had a national following, due in part to a multi-state radio show, albums of his sermons, and appearances around the country.

Franklin who had been elected chairman of a newly-formed group called the Detroit Council for Human Rights, organized to plan a rally in Chicago and then the March to Freedom in Detroit. While there was bickering and in-fighting among the new group and more established civil rights organizations in Detroit, like the NAACP, ultimately most of the Black community came out in support of the June 23 event.

Reuther had a history of backing the civil rights movement and also supported King’s efforts with UAW resources and money. He issued a memo to each of the UAW’s local leaders strongly urging them to mobilize their membership in support of the march in Detroit.

When the day arrived, King flew in from Washington D.C. and marched along side Franklin, Reuther and Cavanagh. They did not actually lead the march; due to the overwhelming numbers, many marchers stepped off early. The atmosphere was festive, and many marchers sang songs along Woodward Avenue, including “We Shall Overcome” and “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The program at Cobo Arena later that day included music from the Four Tops, Erma Franklin, Ramsey Lewis and Dinah Washington interspersed with speeches from Cavanagh, Reuther and Detroit church leaders.

Dr. King speaks at Cobo Arena, June 23, 1963 (Reuther Library, WSU)

Dr. King speaks at Cobo Arena, June 23, 1963 (Reuther Library, WSU)

Finally, King stepped to the podium, thanked Reverend Franklin and noted the Emancipation Proclamation signed 100 years before. He then shared his visions for the future.

“I have a dream this afternoon that one day, right here in Detroit, Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere that their money will carry them, and they will be able to get a job.

“This afternoon, I have a dream,” King continued. “It is a dream firmly rooted in the American dream. I have a dream this afternoon that my four little children – that my four little children will not come up in the same young days that I came up within, but they will be judged on the basis of the content of their character, not the color of their skin.”

While many have claimed that King’s Detroit speech on June 23 was the first time he used the “I have a dream” references, that has been proven inaccurate by a study of King’s speeches by Drew D. Hansen in his 2001 book “The Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Speech That Inspired a Nation.” Hansen notes the earliest known allusion to “I have a dream” dates back to a speech in North Carolina in November 1962, and that the phrase became part of a set piece that King delivered throughout the spring and summer of 1963.

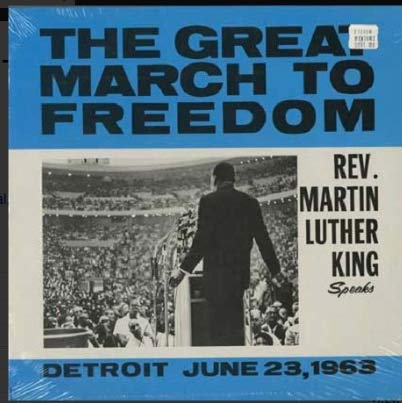

Motown Records LP of the speech (Motown Records)

Motown Records LP of the speech (Motown Records)

No one has been able to confirm if Motown Records founder Berry Gordy was in attendance at the Detroit March to Freedom or King’s speech at Cobo Arena. However, he was sufficiently moved by the speech to release a recording of it in August 1963.

Ultimately, the event was a success. Franklin and King were able to raise over $100,000 for the SCLC. A civil rights bill was delivered to Congress by President Kennedy; it was signed in 1965 by his successor, Lyndon Johnson.

In 2013, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March to Freedom, Martin Luther King, III and other Black civil rights leaders like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton gathered in Detroit to march again down Woodward Avenue, remembering the event as a milestone in the struggle for equality in America.

Bibliography

McGraw, Bill. “Forgotten History: C.L. Franklin’s Battle to Stage Detroit’s 1963 March to Freedom.” Deadline Detroit, June 18, 2013.

Clemens, Elizabeth. “Detroit’s Walk to Freedom.” Walter L. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, June 16, 2011.

Adams, Biba. “Martin Luther King Jr.’s Iconic Impact on Detroit.” VisitDetroit.com, January 18, 2021.