CIVIC AFFAIRS

Henry Leland’s renown as a master machinist and auto pioneer, locally and internationally, was matched by his influence in local politics and civic affairs. An active philanthropist, he donated an annex to Grace Hospital in Southwest Detroit and contributed to local YMCAs, the Detroit Tuberculosis Home, the Salvation Army, and the Boy Scouts. He also supported national charities, including the Florence Crittenton Homes and the Tuskegee Institute.

A prominent Republican, he served in the leadership of the Anti-Saloon League and the Detroit Citizens League, serving as its president for a dozen years. That effort mobilized churches and business leadership in campaigns of moral uplift to oppose political corruption and what it regarded as the unsavory influence of saloonkeepers. The Citizens League reformed the School Board in 1916 and championed the new city charter of 1918. Leland joined with other business leaders in mobilizing support for American involvement in World War I.

He was also was among the business leaders who initially sought to replace street railways with motor buses, superhighways, and fixed-rail rapid transit rather than municipalize the Detroit Urban Railway. That put him at odds with Mayor James Couzens, a former Ford executive, in a political imbroglio that dominated local politics for decades.

This 1919 Detroit News cartoon included the caption - “I wish a law could be passed prohibiting anybody from criticizing the street car company in the future” – Henry M. Leland

This 1919 Detroit News cartoon included the caption - “I wish a law could be passed prohibiting anybody from criticizing the street car company in the future” – Henry M. Leland

THE OPEN SHOP & THE RIGHTS OF LABOR

For those who access this page from the Guide's Labor Roots section, be sure to review the Lincoln Motor Company profile found in the Firms & Sites section for insights into Leland's pioneering enginering accomplishments.

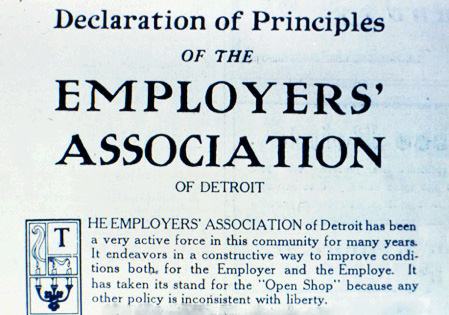

Leland was also one the leading figures in the Employers’ Association of Detroit at the dawn of the 20th century. What constituted the prerogatives of management and the rights of workers was as controversial as it is today (if not more so).

In that era, the debate pitted the “Open Shop” (in which management was free to operate without the constraints of an agreement with a union over wages, production schedules, and working conditions) versus a “Closed Shop” (in which an employee benefitting from the terms of a union contract had to be a member as a condition of being employed at the firm). The lockouts and strikes that characterized the period when the Employers Association of Detroit sought to undermine the standing of unions were bitter conflicts. The violence that erupted as police escorted strikebreakers or enforced injunctions against union members and their sympathizers made front page news.

In a May 5,1906 Detroit News article headlined, "It's a Battle to the Death, Says Leland. Declares Employers Will Quit Detroit if Open Shop Fails," Leland rallied open-shop printing firms with strong language that advocated fleeing Detroit if the police and Army failed to protect property and prevent the unions from regaining power. "If the open shop should fail to hold its own in the city of Detroit,” Leland said, "there will be no need of the laboring man coming to our city, because there will be nothing to do. I would say to you open-shop compositors gathered here the same as I did to some of my men the other day, that if there is a law in this land to protect you we will see that it is enforced. We will call in the police and if that is not enough we will call out the soldiers, and then if it becomes necessary to close the shop it will become a deserted shop and we will go to a climate where they will protect the rights of man.”

While Leland recognized that there were bad employers whose workers needed protection, he saw most employers as decent, honest, and fair. In his biography, Masters of Precision, he offers these thoughts:

“If tonight it was a question if every trade union in Detroit should be abolished, then I would stand with my rifle if necessary and say No! you don’t do it. Because that is the only weapon they have against the unscrupulous employers. Because there are many employers so unscrupulous that if it were not for the organization they would have been crushed, perhaps just as the agitators picture it. Therefore, we must have organized labor, but we must have organized employers.” (1911)

“During my years as an employer I have always and constantly striven to increase wages. I have gone through several [economic] panics in which I have sweat blood to keep the men employed …. I do not believe any man can say that during all that time I have treated my employees with anything but justice and consideration. Some of you know that the most humble employee who has a grievance is welcomed at the president’s office.”

Leland no doubt viewed himself as a good employer, though we don’t know if his workers really were afforded the opportunity to express themselves fully and freely. As is still the case today, many employers insist that their employees have no need for a union.

Click to view

Detroit on Wheels, an excerpt from Steve Babson’s book Working Detroit. It explores the contested terrain between employers and labor in the early years of the auto industry during Detroit’s Open Shop era.

Right To Work Comes to Michigan, the Guide’s overview of the 2012 legislative debate during the administration of Governor Rick Snyder, shows how the balance of power on this long-contested issue shifted back in employers’ favor.

TEXT - DIANNE FEELEY & RON ALPERN

PHOTO CREDITS

Detroit Historical Society

Henry Leland