by A. Wayne Ferens

Images Courtesy of the Tremulis Archives and the Wayne Ferens Collection

Published 10.21.2020

Master Sergeant Alex Tremulis at the drawing board at Wright Field during World War II. (Tremulis Archives)

Master Sergeant Alex Tremulis at the drawing board at Wright Field during World War II. (Tremulis Archives)

Alexander Sarantos Tremulis (1914-1991) was a Greek-American industrial designer who held automotive design positions at the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Company, General Motors, Tucker, Crosley, Kaiser-Frazer, Packard and Ford Motor Company. He worked on hundreds of projects in his 45-year career in the auto business and for dozens of clients as well.

At 19 without any formal training in art or engineering (aside from some art classes at GM's training school), he took his natural talents, enthusiasm and determination to Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg in 1933 as a member of their design team. In 1936, he became Chief Stylist for his contributions to the design of the Duesenberg 810 and 812 series cars. After A-C-D folded in 1937, he briefly worked for GM, Briggs-LeBaron and then as a consultant for several other companies until the United States entered World War II.

Tremulis joined the U.S. Army Air Force in 1941 and was assigned to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, where he worked in the Aircraft Laboratory on Creative Advanced Designs of Aircraft through the use of wind tunnels. After the war, he joined the design firm of Tammen & Denison until Preston Tucker hired him to design the rear-engined 1948 Tucker Sedan. It wasn't until he joined the Ford Motor Company that he could apply his design philosophy combining the smooth flowing lines of an aircraft with the automobile, testing them in a wind tunnel.

By the mid-1950s, many designers felt that the horsepower race was ending for production cars, due to the many accidents and deaths on race tracks around the world. Tremulis felt that progress in automotive design must be made by better streamlining with regard to basic body shapes and forms, and in order to be fairly evaluated, must be tested in a wind tunnel.

To convince Ford management to support his design philosophy, he presented them with dozens of examples comparing different models in performance, directional stability and economy. For example, he stated that there was little or no progress in drag reduction since the 1930s. The 1937 Lincoln Zephyr had a coefficient of drag much lower than the new 1953 Lincoln, and a 140-hp Zephyr would match the present 205-hp Lincoln in speed. The 1949 Ford, due mainly to a frontal area reduction of some 2.5 square feet showed an increase of 5 mph over the 1948 Ford. The 1953 Ford was 3 mph slower than the 1949 in spite of a power increase due to an increase in drag coefficient. His goal was to design better, more attractive streamlined cars, consuming far less horsepower with greater stability and economy. Management at the Special Projects Department and the Engineering Staff were convinced.

In June, 1954, a proposal was made for a preliminary investigation of the possibility of obtaining aerodynamic information using 3/8 scale model cars. To minimize costs, Ford had the facilities and instrumentation already available for this work at their Vehicles Testing Department in Dearborn. It was also determined that the information acquired from the model tests done in Ford’s wind tunnel would check very well with road tests of full size cars.

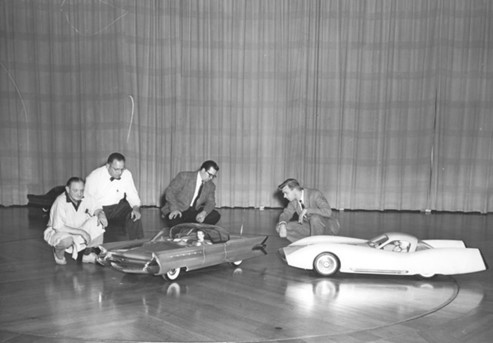

The Ford design team with models La Tosca and Mexico on display at the Ford Rotunda. The La Tosca would evolve into the design for the 1958 Lincoln. (Tremulis Archives)

The Ford design team with models La Tosca and Mexico on display at the Ford Rotunda. The La Tosca would evolve into the design for the 1958 Lincoln. (Tremulis Archives)

General Motors introduced a newly designed V8 Corvette for 1956 that put emphasis on style and performance. Ford and Chevy were in the midst of a speed war at the time. The rumor was Chevrolet was preparing a modified Corvette for an assault on the high-speed record in February, 1956 at Daytona Beach, Florida. Ford engineers knew that the drag coefficient of the new Thunderbird was very high at CD=.62, so in order to be competitive and reach a 150 mph speed at Daytona, the T-Bird engine would have to produce around 330-hp. Even with a supercharger, the OHV V8 Thunderbird engine would only produce about 270-hp. Tremulis felt that special aero-modifications would make it competitive. These modifications would consist of a single enclosed bubble canopy with a fiberglass tonneau fairing, a fiberglass upswept underpan (that would cancel out the high lift aerodynamic forces), and a modified headlight bezel.

There were two parts to the Daytona event: standing-mile acceleration and top speed. The John Fitch Corvette came in third behind Chuck Dalgh's 86.872 mph modified T-Bird in the standing mile. The Dalgh T-Bird didn't compete in the top-speed runs. The Fitch Corvette won the production-sports-car class with a top speed of 145.543 mph. (Ferens Collection)

There were two parts to the Daytona event: standing-mile acceleration and top speed. The John Fitch Corvette came in third behind Chuck Dalgh's 86.872 mph modified T-Bird in the standing mile. The Dalgh T-Bird didn't compete in the top-speed runs. The Fitch Corvette won the production-sports-car class with a top speed of 145.543 mph. (Ferens Collection)

There were two parts to the Daytona event: standing-mile acceleration and top speed. The John Fitch Corvette came in third behind Chuck Dalgh's 86.872 mph modified T-Bird in the standing mile. The Dalgh T-Bird didn't compete in the top-speed runs. The Fitch Corvette won the production-sports-car class with a top speed of 145.543 mph. Photos from Ferens collection.

Tremulis originally built three 3/8 scale models for his initial wind tunnel tests. A 1955 Ford two-door sedan that was used as the baseline by which all the other design changes could be compared, a concept car he called the Taj Mahal and his Thunderbird Mexico race car. In addition to these three basic designs, by adding on bits and pieces to these models, the effects of various components intended to reduce drag could be evaluated. Tremulis loved the design concept using fins, and wind tunnel tests did show more stability with rear fins that would grace so many of the cars of the late 1950s. They were not only stylish, but functional.

The Thunderbird Mexico would prove its worth in the wind tunnel. Its design would indicate that the Mexico would only require half the horsepower to overcome wind resistance at 120 mph over the standard 1955 sedan. That meant that the Mexico would have an additional 70-hp to use for acceleration and top speed. The ground effects of its full bellypan were shown to be very beneficial in reducing drag. Top speed estimates for the Mexico were in the 200 mph range.

Alex Tremulis with his 3/8 scale model he named the Thunderbird Mexico. It was estimated a full size version would hit speeds around 200 mph. A full size car was never built. (Tremulis Archives)

Alex Tremulis with his 3/8 scale model he named the Thunderbird Mexico. It was estimated a full size version would hit speeds around 200 mph. A full size car was never built. (Tremulis Archives)

Tremulis worked at Ford starting in 1952, first working in the Mercury studio then in the Gil Spears Advanced Studio that he would head from 1954 to 1956. During his tenure at Ford, Tremulis and his team would design such notable concepts as the Mystere, the Lincoln Futura, the three-wheeled Maxima, the bubbletop X-2000, the two wheeled Gyron, the six-wheeled Seattle-ite XXI and the Ford Nucleon.

Tremulis left Ford in 1962 and started his own consulting and design firm. He designed race cars and motorcycles including the 1966 Gyronaut X-1 that set the worlds record for motorcycles at 245.667-mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats.

The X-1 tailfin was criticised by those who knew nothing about aerodynamics and pressures on a high-speed vehicle until it set the world's record for motorcycles that was held for four years. (Ferens Collection)

The X-1 tailfin was criticised by those who knew nothing about aerodynamics and pressures on a high-speed vehicle until it set the world's record for motorcycles that was held for four years. (Ferens Collection)

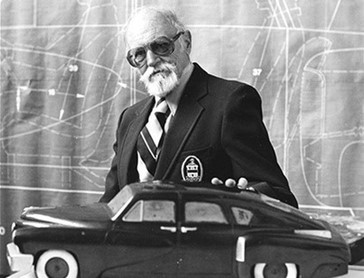

Tremulis with the 1948 Tucker scale model he designed for the visionary Preston Tucker who was also inducted into the Auto Hall of Fame in 1999. Only 50 cars were made before the company ceased operations on March 3, 1949. (Tremulis Archives)

Tremulis with the 1948 Tucker scale model he designed for the visionary Preston Tucker who was also inducted into the Auto Hall of Fame in 1999. Only 50 cars were made before the company ceased operations on March 3, 1949. (Tremulis Archives)

In 1982 Tremulis was awarded the Distinguished Service Citation by the Automotive Hall of Fame and was inducted into the AHOF in 2014 with honors from the Society of Automotive Engineers. Looking back at his accomplishments, he would often say “My wildest feelings of excitement and raw pleasure come from anticipating what that car, the car of tomorrow, will be..."

Bibliography:

Ferrell, Cheryl and Jim. “Ford Design Concepts & Show Cars.” 1999.

“Dream Cars, Show Cars and Prototypes.” Hemmings Archives

Pearson, Charles. “Indomitable Tin Goose.” 1960.