The First Revolutionary Union was organized by Black workers at the Dodge Main plant in Hamtramck. Several wildcat strikes had happened at this plant in 1967 and early 1968 to “protest increased production levels and harsher management discipline”. The wildcat that led to the creation of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) happened on May 2, 1968. James A. Geschwender claims that the exact cause of the wildcat is uncertain:

One frequently heard version of events states widespread discontent existed among workers over a speedup in the line. This speedup was only one of many sources of dissatisfaction. There existed a small interacting group of Polish women who worked in the same department, belonged to the same Rosary Society, and generally socialized together both inside and outside the plant. For some unexplained reason their discontent reached a peak on May 2 and they decided to walk off the job. Other persons, who were also dissatisfied over the speedup and otherwise unhappy, joined them and the wildcat was on. While they are not incompatible with this interpretation, there are other versions. […] Lee Cain, a black worker who did not join DRUM, admits to having played a major role in the organization of the walkout. Detroit newspapers have generally attributed the wildcat to DRUM leadership. It would appear that the wildcat was somewhat spontaneous and led by a coalition of forces.

Most Dodge workers honored the picket lines. It has also been clearly established that the company punished black workers disproportionately after the strike ended even though the strike was interracial. Frustrated by the disproportionate character of these punishments, nine workers decided to found DRUM to fight against the racial discrimination encountered in plants by Black workers and, more broadly, the overall discrimination of Black workers. They also created a weekly newsletter entitled drum to describe episodes that testified to a climate of racism or to bad working conditions, and to foster a sense of community among workers. The second issue of drum explained, importantly, why a separate entity outside the UAW union structure was deemed necessary:

DRUM picket line 1968

DRUM picket line 1968

“The justification stated that 60 percent of the work force at the Hamtramck assembly plant (Dodge Main) were black, that these black workers worked under inhumane conditions, and were exposed to racist practices. It further charged that the UAW leadership was as guilty as management of perpetuating a racist system. It claimed that black workers had consistently addressed grievances to the UAW without receiving any satisfaction.”

In the months following the creation of the drum newsletter, DRUM organized several successful actions that led to its popularity among Black autoworkers. These successes inspired Black rank-and-file workers to create Revolutionary Unions in various Michigan auto plants, for example, FRUM at Ford, as well as ELRUM at Chrysler’s Eldon Avenue plant. Revolutionary Unions were formed in other states and other workplaces and industries as well, such as healthcare workers and at United Parcel Service. As Revolutionary Unions appeared across the nation, the need for a central coordinating organization became evident: the League of Revolutionary Black Workers was established in 1969 and began publishing the newsletter Spear. When financial means allowed it, the League brought back to life the Inner City Voice – a Black radical newspaper created around the time of the Detroit Uprising of 1967. Many of the Black radicals that had been associated with the Inner City Voice had become the founders of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, together with Revolutionary Union leaders.

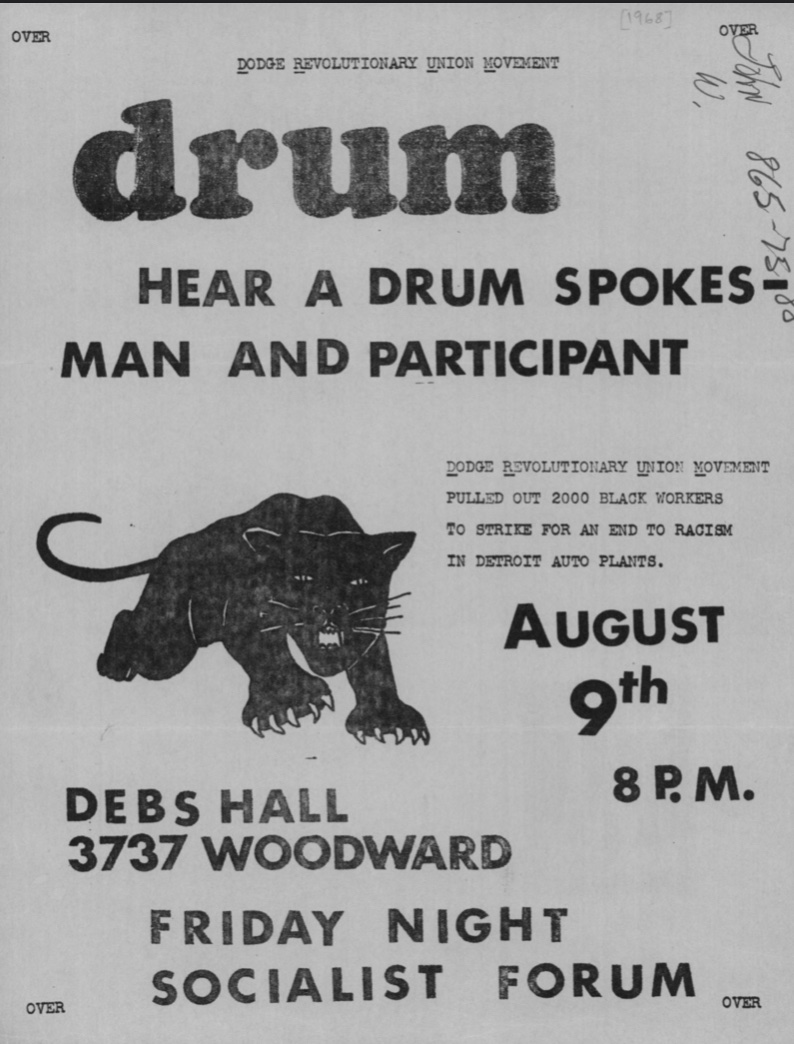

DRUM Flyer 1968

DRUM Flyer 1968

James Geschwender describes the League’s role in precise terms:

“The League functioned as an integrative body coordinating general policy, political education, and the strategies for its various components. A number of black student groups were formed and directly affiliated with the League. The League acted as a forum for the discussion of ideas and plans but did not issue directives to any of its components.”

The League was thought of as a Black Marxist-Leninist organization: this is unsurprising, given the fact that an important number of Marxist groups had had various activities in Detroit in the forty years preceding the League’s creation. Third-World revolutionaries such as Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, Mao Tse-tung, Frantz Fanon, and others, inspired the League’s revolutionary nationalism; the perception that the difficulties faced by Detroit autoworkers could be conceived according to a broader anti-capitalist and anticolonial agenda became essential for the League.

Reactions to the Revolutionary Union Movement were mixed. Some of the negative reactions to the Revolutionary Unions were due to a racialized rhetoric chosen to respond to the racism endured by Black autoworkers:

“Revolutionary Unionists referred to whites as “honkys” […] DRUM attacks on whites often had an ethnic cast, because of the presence of many Polish immigrants and workers of Polish ancestry in the Dodge Main plant. Hamtramck, where the plant was located, was a predominately Polish-immigrant city where many of the police and local union officials claimed Polish ancestry. In one of its newsletters, ELRUM informed a white worker, Stan Marcinowski, that if he continued to harass black women, “[Y]ou will find yourself jammed up in a jar of Polish sausage.” DRUM also regularly referred to the Hamtramck police as “Polish pigs.” Such methods and ethnicized discourse were at the source of the vigorous opposition the Revolutionary Unions faced, for example, from the liberal anti-communists who were at the center of the Trade Union Leadership Council (TULC).

The Revolutionary Unions also endorsed forms of violent resistance, which oriented the UAW’s response to their actions: “By 1969, a year after the emergence of the DRUM challenge in the union, the UAW […] led a direct assault on black-power activists in the union.” An important number of white workers on the shopfloor also reacted negatively to the Revolutionary Union Movement.

The paternalistic attitude some of the Revolutionary Union men adopted towards their Black female coworkers, seeking to protect them not only from difficult working conditions, but from other hardships as well – the sexual exploitation in the auto plants the Revolutionary Union men perceived their coworkers faced, among others – was also source of discomfort for many African American women who actively sustained the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. David M. Lewis-Colman explains how, responding to what they perceived was a sexist attitude prevalent in the Revolutionary Union Movement, some women activists who were very involved in the League – albeit often without seeing their contributions properly recognized – started demanding representation on the League’s executive board and appreciation for their essential role. He mentions the names of Edna Ewell Watson, Marian Kramer, Cassandra Smith, and Gracie Wooten. Edna Ewell’s contribution is especially underlined:

“The resources Edna Ewell had accumulated through her income as a nurse sustained League organizing; the League could not have functioned without access to her house, car, and bank account. Ewell’s house was, in her words, “a crash pad for the movement,” hosting important figures in the black freedom struggle, including Fannie Lou Hamer, James Forman, and the Spanish Civil War veteran Harry Haywood. Ewell’s car carried activists to meetings and rallies, and her bank account helped fund the movement.”

The preceding remarks do not intend to mask the positive responses to the Revolutionary Union Movement. David M. Lewis-Colman writes that “black leftists who had roots in the Negro-caucus struggles of the 1940s and early 1950s were most likely to appreciate the connections between the Revolutionary Union insurgency and their earlier activism and offer concrete support to the young militant black autoworkers.” In considering DRUM’s and the League’s legacy, the 12th Street Detroit Web Exhibit mentions, among others, that both “forced the UAW to face its own systematic racism” and “improved working conditions in factories around Metro Detroit.” Auto companies also hired more black foremen and plant managers, at least partly as result of the Revolutionary Unions’ actions. The Revolutionary Union Movement helped Black workers get elected to local union office, and, more broadly, empower African Americans of Detroit in the political sphere.

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

-“Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement.” 12th Street Detroit Web Exhibit (Walter P. Reuther Library), https://projects.lib.wayne.edu/12thstreetdetroit/exhibits/show/aftermathofunrest/drum. Accessed 18 March 2022.

-Georgakas, Dan and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, Cambridge (Mass.), South End Press, 1998, 254 p.

-Geschwender, James A. Class, Race, and Worker Insurgency. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1977, 250 p.

-Lewis-Colman, David M. Race against Liberalism. Black Workers and the UAW in Detroit, Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2008, 150 p.

[1] David M. Lewis-Colman, Race against Liberalism. Black Workers and the UAW in Detroit, Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2008, p. 97.

[1] James A. Geschwender, Class, Race, and Worker Insurgency. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 88-89.