Although Detroit cherished a perception of itself as a “model city” in the way it dealt with race relations in the 1960s, its African American residents clearly faced various forms of discrimination in that time that contributed to the urban unrest that took place in the summer of 1967. Police brutality and harassment was one of the most important of these. Housing was also a major issue:

“By the 1960s, despite the movement of some blacks into formerly white neighborhoods, segregation had become more pronounced. The quality and cost of housing differed substantially for blacks and whites in Detroit, with black residents paying considerably higher rents than their white counterparts for equivalent accommodations. Only 39 percent of African Americans owned their own homes in 1960, as compared with the 64 percent of whites who were homeowners.”

So-called “urban renewal” projects only worsened the situation for black residents of Detroit. Neighborhoods that were primarily black such as “Black Bottom” – which was then the heart of Detroit’s black cultural and financial life – were demolished to build freeways. Residents of these neighborhoods were often unable to move anywhere else in Detroit: “the city already had a housing shortage, they often could not afford the new housing developments, and many banks would either offer loans to black Detroiters at unfavorable rates or refused to offer them loans at all.”

In the workplace, black residents also faced discrimination and various difficulties. The automotive industry’s example is revealing: “Beginning in the 1950s, the big car manufacturers, Ford, Chrysler and GM, began to automate their assembly lines and outsource parts production to subcontractors located in other municipalities and foreign countries. Detroit, like other cities, was deindustrializing and black workers, who had less seniority and lower job grades than white workers "felt the brunt" of this change.” These changes affected particularly young black workers, who became aware that the opportunities the automotive industry had offered their older siblings in the past decades had disappeared. As jobs began to relocate to suburban areas, white residents also had a better access to these since more white than black residents had been able to afford moving to these areas. A surge of white flight affected Detroit: throughout the 1950s, the white population of Detroit diminished by 23%, and some neighborhoods went through a particularly massive white flight accompanied by disastrous societal effects. This was the case for the 12th Street neighborhood where the urban uprising of 1967 erupted and in which the swift demographic turnover was accompanied by “the ills of social disorganization, crime and further discrimination.”

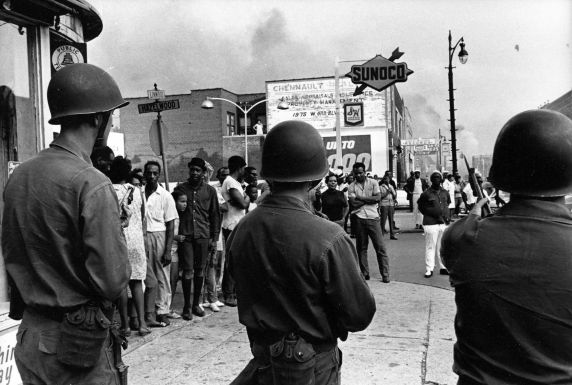

National Guardsmen face citizens July 1967 image courtesy of Walter Reuther Library

National Guardsmen face citizens July 1967 image courtesy of Walter Reuther Library

For all these reasons, the urban uprising did not come as a total surprise: rumors pertaining to a possible unrest had been circulating throughout the city, and local militants in the black community freely evoked the ideas of self-determination and separatism for black people. The trigger event that caused the urban uprising, though, was the arrest in the early morning of Sunday, July 23, of 85 African Americans during a random raid by the Detroit Police Department at a “blind pig,” located at 12th Street and Clairmount Avenue, a community after-hours bar that did not possess an alcohol license. Instead of making only a few arrests, the police officer who was in charge decided to arrest all 85 people who were present on scene. Thomas J. Sugrue describes what happened only shortly after:

Burning buildings light up the night sky on Detroits west side image courtesy of Walter Reuther Library

Burning buildings light up the night sky on Detroits west side image courtesy of Walter Reuther Library

“By four in the morning, an hour after the bust, nearly 200 had gathered to watch the proceedings. As the arrestees shouted allegations of police brutality, tempers rose. The crowd began to jeer and to throw bottles, beer cans, and rocks at the police. William Scott III, a son of one of the blind pig’s owners, threw a bottle at a police officer and shouted, "Get your goddamn sticks and bottles and start hurtin’ baby." By 8 a.m., a crowd of over 3,000 had gathered on 12th Street.”

Over the next days, vandalism, looting, and fires continued through the northwest side of Detroit, then crossed to the east side, spreading over nearly one hundred square miles. While the National Guard was called on within 48 hours, neither its intervention nor the imposition of a curfew between 9 p.m. and 5:30 a.m. were sufficient to contain the situation. The 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions were also mobilized.

Entire city blocks were set ablaze, and fires continued throughout the five days of the uprising: on Monday, July 24, the worst day in terms of number of fires, 483 fires took place. The 12th Street Detroit Web Exhibit explains how the situation deescalated:

Image courtesy of the Walter Reuther Library

Image courtesy of the Walter Reuther Library

“As tanks rolled through the city and widespread food shortages took their toll, the chaos began to dissipate. Sniper fights, fires, and small outbursts of violence continued sporadically until July 27, when the conflict officially ended. In the end, the Civil Unrest of 1967 proved to be one of the most destructive civic events in the nation’s history, exceeded only by the Los Angeles Riots of 1992 and the New York City Draft Riots during the Civil War. Over 465 people were injured and 43 people lost their lives, the youngest only four-years old. Property damage exceeded an estimated 50 million dollars, with 2,509 stores burned or looted and 388 families displaced by fire.”

Most of the deaths were the result of the city police force’s action or that of the Michigan National Guard: “The police were especially brutal, beating arrestees and in one case vandalizing and fire-bombing a black-owned shop. Three police officers, responding to rumors of sniping, raided the city’s Algiers Motel and executed three young black men on the premises, none of them participants in the uprising.”

The insurrection of the summer of 1967 in the Motor City was the most violent uprising of the 1960s in the United States. Thomas J. Sugrue has firmly suggested, however, to invalidate the perception of the Detroit 1967 uprising as “a moment of collective lawlessness and disorder or as an irrational outpouring of rage.” In his view, “To use the contested language of the 1960s, black Detroiters engaged in an uprising against a racially unequal status quo, a rebellion against brutal police and exploitative shopkeepers. […] Many of the participants in the 1967 riot took the opportunity to exact revenge for economic hardship. Looters singled out merchants, especially owners of food stores who routinely overcharged their inner-city customers. Some saw looting as redistributive justice.”

One example of the unrest’s effects was that the Detroit Common Council passed the Fair Housing Ordinance in 1967, which protected citizens against various forms of racial or ethnic discrimination in the leasing and sale of property.

While Detroit had the most violent of the 1960s insurrections in the United States, that same summer, 163 other towns and cities burned in America.

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

-“12th Street Detroit Web Exhibit.” Walter P. Reuther Library, https://projects.lib.wayne.edu/12thstreetdetroit/exhibits/show/beforeunrest/panel5 . Accessed 10 February 2022.

-HERMAN, Max. Riots – 1967, https://web.archive.org/web/20140401034826/http:/www.67riots.rutgers.edu/d_index.htm . Accessed 10 February 2022. (See also his monograph on the subject: Max Arthur Herman, Fighting in the Streets. Ethnic Succession and Urban Unrest in Twentieth-Century America, New York, Peter Lang, 2005, 184 p.)

-“How the 1967 riots reshaped Detroit, and the rebuilding that still needs to be done.” PBS News Hour,

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/1967-riots-reshaped-detroit-rebuilding-still-needs-done#transcript. Accessed 11 February 2022.

-STONE, Joel (ed.). Detroit 1967. Origins, Impacts, Legacies, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 2017, 328 p.

Max Herman, « Housing. » Riots – 1967, https://web.archive.org/web/20140401034826/http://www.67riots.rutgers.edu/d_index.htm . Accessed 10 February 2022.

« The Effects of Urban Renewal. » 12th Street Detroit Web Exhibit/Walter P. Reuther Library, https://projects.lib.wayne.edu/12thstreetdetroit/exhibits/show/beforeunrest/panel5 . Accessed 10 February 2022.

Max Herman, “Economic Inequality/Relative Deprivation.” Riots – 1967, https://web.archive.org/web/20140401034826/http://www.67riots.rutgers.edu/d_index.htm . Accessed 10 February 2022.

Max Herman, “Demographic Change.” Riots – 1967, https://web.archive.org/web/20140401034826/http://www.67riots.rutgers.edu/d_index.htm . Accessed 10 February 2022.