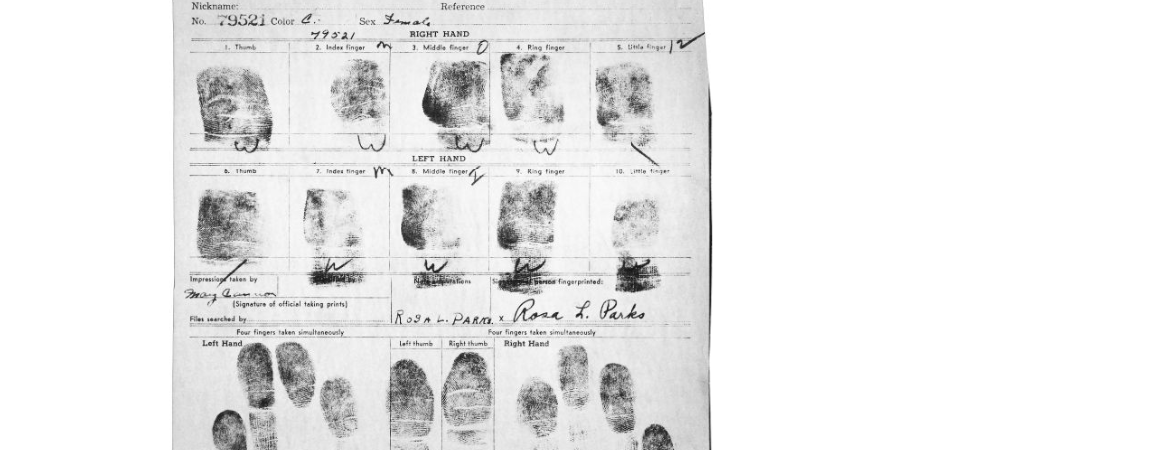

On December 1, 1955, Mrs. Rosa Parks (born McCauley), a seamstress at the Montgomery Fair department store in Montgomery, Alabama, left the store to go back home, getting on a bus and taking the only remaining vacant seat next to the aisle, in the front row of the “colored” section. At the third stop, when the bus driver pulled up to the side of the Empire Theater, a number of white passengers entered the bus and the “lily-white” section became full. One white man had to remain standing. The bus driver J.S. Blake requested from the first-row passengers of the colored section: “You let him have those front seats!” When none of the black passengers moved when first called upon, the bus driver reiterated his request, this time more firmly: “You all better make it light on yourselves and let me have those seats.” Three of the four passengers stood up, but Mrs. Parks didn’t. The bus driver then came down the aisle to go in Mrs. Parks’ direction and asked her if she was going to get up, but Mrs. Parks replied “No.” “I’m going to have you arrested,” the driver said. “You may do that,” she answered. Two white policemen arrived. She asked one of them, “Why do you all push us around?” He answered, “I don’t know, but the law is the law and you’re under arrest.” The police took her to the jail where she was fingerprinted, photographed and booked.

Rosa Parks' fingerprints image courtesy of the National Archives

Rosa Parks' fingerprints image courtesy of the National Archives

E.D. Nixon, who had been a community leader in many civil rights causes in Montgomery, bailed her out of jail. He was the former head of the Montgomery branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1946-50) and former head of the state NAACP conference (1947-1949); Parks had worked with him for a dozen years in the NAACP. Indeed, Rosa Parks was a civil rights activist who had been one of the first women in Montgomery to join the NAACP, serving as the secretary of the Montgomery branch and having also been involved in the Alabama State branch. She was fully aware of the consequences her refusal to stand up to leave her seat on the bus could have entailed. She knew of numerous previous cases where black passengers had been beaten or even shot by the police or bus drivers when they were unwilling to comply with the segregation laws on public transportation. She had herself confronted bus segregation laws in the past since “she had refused to put her fare in the front fare box and go around to the back door to reenter the bus.”

Nixon asked Parks that night for permission to use her bus arrest as a case to measure the constitutionality of the local city bus ordinance: “The policy of the Montgomery City Lines bus company was written in keeping with city and state ordinances on segregation. Drivers were to designate the front part of the bus for whites and the rear section for blacks in proportion to the number of blacks and whites on the bus at any given moment. As more whites came onto the bus, the driver moved an imaginary color line further to the rear of the bus. Blacks, sitting directly behind the ‘whites-only’ section, would be ordered to move further toward the rear of the bus, if whites had to stand. The official policy, theoretically, was that if there were no vacant seats available behind the imaginary color line, blacks did not have to stand for whites to sit. But, in practice, whenever a white person had to stand, the driver would look in the rear view mirror and yell at the ‘Nigras’ to move to the back of the bus, even if there were no vacant seats.” The racist system on buses had been an issue for many years, with women making “all of the litigants who challenged the racist system, in the courts” – since most of the black passengers on buses in Montgomery were women, this isn’t surprising. Nixon had previously tried to find a representative case to question the legality of the city bus practices. However, he had never found a case or a person he believed solid enough for the black community of Montgomery to coalescence around to attempt a confrontation of the city buses. However, with Parks, he thought that he had a powerful person to rely on, since she was highly known and respected in the black community of Montgomery. After much thought and a discussion with her husband, Parks agreed to have Nixon use her case and name to support the battle for an integrated public transportation system.

In fact, preparation to organize a bus boycott in Montgomery had already begun many months before through other members of the black community, specifically, at the Women’s Political Council (WPC), which was formed in 1949 after Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, a professor at Alabama State College, was forced to leave an almost empty bus when she refused to move to the back. The WPC also considered the arrest of Parks as the appropriate event to set a boycott in motion. With the help of two of her senior students, Robinson printed out leaflets with their college’s mimeograph equipment in the middle of the night from December 1st to December 2nd asking every black person to stay off the Montgomery buses on Monday December 5, 1955, the day of Rosa Parks’ trial, as a protest of the trial. By the evening of December 2nd, many Black citizens of Montgomery had already received the leaflet. Nixon had worked hard on the morning of December 2nd to reach out to local leaders in the black community – first turning to the churches. A group of these preachers decided to organize a meeting that evening:

“More than 50 people met in the basement of Dexter Avenue Baptist church. They represented every segment of the black community: ministers, doctors, lawyers, businessmen, teachers (primarily from Alabama State College), unskilled and semi-skilled laborers, students, heads of political, professional and social clubs, men and women, all were represented.” Parks was also present and told everyone what had happened to her. The group’s members, while not of the same mind about all different matters discussed that evening, agreed that a form of collective action had to take place and outlined some measures that had to be taken to ensure that the widest audience possible would be reached in the black community. These measures included, among others: telling everyone in the black community what had happened to Parks on the bus; asking everyone to support the bus boycott on Monday; and that the bus boycott would be the only sermon delivered by the ministers on Sunday, December 4.

Dedication of Rosa Parks Blvd in Detroit, July 1967 image courtesy of Library of Congress

Dedication of Rosa Parks Blvd in Detroit, July 1967 image courtesy of Library of Congress

The boycott was an immense success: “Scarcely any African Americans rode the buses on Monday, December 5.” At the sight of this first day’s success, the leaders of the black community then formed a new entity, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), and chose Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as their leader. On a mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church on December 5, they decided to pursue the boycott – a boycott that, in the end, would end up lasting for three hundred and eighty-one days. During the boycott, African Americans carpooled or walked to work, to run errands, or to attend their other daily activities, while facing harassment and bullying or even the loss of their jobs. In February 1956, the MIA filed a lawsuit in federal district court challenging the constitutionality of bus segregation. In June, the court ruled in favor of the MIA, but the city appealed the decision to the Supreme Court which, on November 13, 1956, upheld the district court’s ruling that bus segregation violated the equal protections clauses of the 14th amendment. The city officials of Montgomery challenged the ruling again but were unsuccessful.

Dr. Roberta Hughes Wright writes eloquently about the MIA’s great commitment in this context:

“The boycott, already 343 days old at that time, could have been called off. In a magnificent display of dedication and discipline, the members of MIA continued the boycott for another 38 days until the federal decree reached Montgomery. The written mandate arrived in Montgomery on December 20, and on December 21, 1956, nearly thirteen months from the start, blacks returned to the buses.”

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

Burns, Stewart. Daybreak of Freedom. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, Chapel Hill and London, The University of North Carolina Press, 1997, 359 p.

Parks, Rosa (with Jim Haskins). Rosa Parks: My Story, New York, Dial Books, 1992, 192 p.

“Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott,” Celebrating Martin Luther K. Jr. (at Wesleyan University), https://www.wesleyan.edu/mlk/posters/rosaparks.html . Accessed 2 February 2022.

“The Bus Boycott,” Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words (exhibit/Library of Congress), https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/rosa-parks-in-her-own-words/about-this-exhibition/the-bus-boycott/ . Accessed 2 February 2022.

Wright, Dr. Roberta Hughes. The Birth of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Southfield (Michigan), Charro Book Co., Inc., 1991, 158 p.

In August 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Louis Till traveled from Chicago to visit his uncle and relatives three miles outside of Money, Mississippi. During his visit, Emmett Till went to the Bryant store with his cousins and may have whistled at Carolyn Bryant (accounts vary on what actually happened at the store run by Carolyn Bryant and her husband, Roy Bryant). A few days later, Emmett Till was kidnapped in the middle of the night at his great-uncle Moses Wright’s home, and then tortured and murdered by Roy Bryant and brother-in-law, J.W. Milam, who dumped his body in the Tallahatchie River after having tied a cotton gin fan around his neck. His badly battered and ravaged corpse was retrieved days later from the water.

When Till’s body was brought back to Chicago at the beginning of September 1955, Mamie Till, Emmett’s mother, “focused much of black Chicago on her son’s murder and the movement it could help unleash.” She wanted an open casket for her son and insisted that her son’s body – which remained in a truly dreadful state – shouldn’t be retouched to ensure that the world would witness the brutality of his treatment. At the funeral home, photographer Ernest Withers took a close-up picture of Emmett’s face that was published in Jet magazine on September 15 and became perhaps the photograph with the greatest effect in American Black circles historically – it “was passed around at barbershops, beauty parlors, college campuses, and black churches, reaching millions of people.”

Mamie Till Mobley at son's funeral September 6,1955 image credit AP/Chicago Sun Times

Mamie Till Mobley at son's funeral September 6,1955 image credit AP/Chicago Sun Times

The Mississippi Civil Rights Project’s website explains the circumstances of the legal procedures that took place after of the discovery of Till’s body in the Tallahatchie River: “The Grand Jury meeting in Sumner, Mississippi, indicted Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam for the crime of murder. These two men were then tried on this charge and were acquitted by an all-white, all-male jury after a deliberation of just over an hour. Within three months of their acquittal the two men confessed to the murder. Before the trial began, Till’s mother had sought assistance from federal officials, under the terms of the so-called "Lindbergh Law," which made kidnapping a federal crime, but received no aid. Only a renewed request in December 2002 from Till’s mother, supported by Mississippi District Attorney Joyce Chiles and the Emmett Till Justice Campaign, yielded a new investigation.”

Most recently, on December 6, 2021, the United States Justice department closed the latest investigation on the case, which was reopened after the publication of historian Timothy B. Tyson’s book The Blood of Emmett Till. In this book, the author asserts that Carolyn Bryant recanted her testimony in a 2008 interview; Tyson claims that Bryant told him that the parts of the story she had told at the trial of her encounter with Emmett Till at the store, namely that “Till had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities,” were not true. The Justice Department closed the investigation because Bryant (now Bryant Donham) denied ever recanting her testimony with Tyson in 2008, and the D.O.J. was not able to confirm the book’s statement of her recantation, since Tyson provided only one recording to the F.B.I. which did not include a recantation, even if he said that “although he did not record Ms. Donham’s recantation, he took detailed notes” and that “Carolyn started spilling the beans before [he] got the recorder going.”

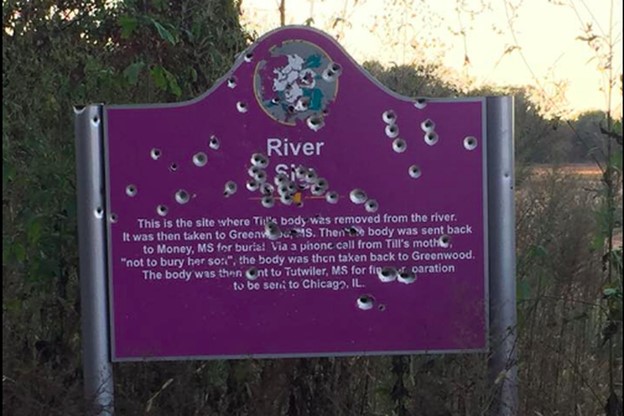

The murder of Emmett Till in 1955 is considered a key event in the civil rights movement, having inspired a number of young activists who feared that their relatives or friends could also be subject to such racial hatred. Additionally, as Philip C. Kolin writes, “Over the decades, Till has become the subject of numerous poems, plays, screenplays, novels, autobiographies, and songs in America and throughout the world.” To get an overview of these, Kolin suggests looking into Harriet Pollock’s and Christopher Metress’ 2008 collection of essays, Emmett Till in Literary Memory and Imagination.

Emmett Till site marker vandalized by gunshots

Emmett Till site marker vandalized by gunshots

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

-Burch, Audra D. S. and Tariro Mzezewa, “Justice Department Closes Emmett Till Investigation Without Charges.” The New York Times, 6 December 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/06/us/emmett-till-investigation-closed.html. Accessed 31 January 2022.

-“Emmett Till Memorial Commission.” Mississippi Civil Rights Project, https://mscivilrightsproject.org/tallahatchie/organization-tallahatchie/emmett-till-memorial-commission. Accessed 31 January 2022.

-Kolin, Philip C. “The Legacy of Emmett Till.” The Southern Quarterly, Vol. 45, no 4, p. 6-8.

-Pollack, Harriet et Christopher Metress, Emmett Till in literary memory and imagination, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2008, 262 p.

-Tyson, Timothy B. The Blood of Emmett Till, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2017, 291 p.

1 Timothy B. Tyson, The Blood of Emmett Till, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2017, p. 67.

2 Ibid., p. 75.

3 “Emmett Till Memorial Commission.” Mississippi Civil Rights Project, https://mscivilrightsproject.org/tallahatchie/organization-tallahatchie/emmett-till-memorial-commission. Accessed 31 January 2022.

4 Timothy B. Tyson, op. cit., p. 6.