It is in the context of public transportation (on buses, streetcars, and trains) that American Blacks were exposed to some of the most brutal forms of racial discrimination from the late nineteenth century through the civil rights movement. In the South, the Jim Crow laws were applied in seating arrangements, waiting rooms and bathrooms, for drinking fountains, etc. Thus, the automobile represented, in the eyes of many African Americans who could afford one, the possibility to break out of the constraints and humiliation of Jim Crow laws. However, traveling by car still represented very serious challenges for American Blacks, who often couldn’t use the bathrooms or restaurants at roadside service stations, for example – while these arrangements were supported by the Jim Crow laws in the South, they also existed elsewhere in the United States. Mia Bay writes: “[…] black drivers learned to assemble Jim Crow kits before driving any distance. They loaded up their cars with food, water, and maps (so they would not have to stop and ask for directions) and carried amenities such as toilet paper and “pee cans,” assuming that they would not be able to use roadside restaurants. Many also filled their gas tanks before leaving home and even carried additional gas in the trunks of their cars. If they had to stop for gas, they tried to time their trips so they could make such stops in major cities.”

Green Book cover page courtesy of Library of Congress

Green Book cover page courtesy of Library of Congress

The necessity of carefully planning one’s trip as an African American motorist is an element on which the early editions of The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide founded by Victor Green in 1936, insisted, focusing for instance on the importance of maintaining one’s car in good condition “to avoid mechanical problems on the road that could leave riders stranded and in a dangerous predicament”. The first issue of the Green Book was published in 1937 by Green and his partner George L. Smith. After Smith’s death, Victor Green secured the collaboration of his brother William, who remained on board until 1945. When Victor retired in 1952, his wife Alma took over the role of publisher while Victor remained her adviser. The Green Book’s goal was to create a geographically organized list of community services and businesses that were welcoming of African Americans, in order to inform them where they would be received, and where they wouldn’t be – which was most helpful for African Americans on the road. Most of the businesses featured in The Green Book were owned by African Americans, but the guide also included advertisements from welcoming white-owned businesses. Initially, the Green Book focused on the New York city area, but it expanded over time, emphasizing major cities in the East, including Cincinnati, Washington, DC, and Baltimore. By the mid-1960s, the book included listings all over America – though states were of course not equally represented: “The Green Book identified relatively few accommodations in South Dakota and Wyoming, which had tiny black populations,” writes Gretchen Sorin. Travel tips, listings of hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, doctors’ offices, drugstores, beauty parlors, barbershops, taverns, and service stations welcoming of black customers, and advertisements for some of the businesses it mentioned were all included in the Green Book. Victor Green’s guide was meant to be appealing to a wide audience across social classes, since it encompassed a variety of establishments: in lodging, for example, he included affordable rooms in YMCAs and various types of accommodations up to hotels.

Gretchen Sorin mentions that Victor Green identified guides written for Jewish travelers as the inspiration for his own, while Mia Bay mentions an additional source of inspiration, the Automobile Green Book, a road guide to the East Coast published by the Automobile Legal Association. A lot of the information contained in the Green Book came from its readers and their own travel experiences as customers, but Green also paid travel agents for their contributions; additionally, the publisher sent out annual letters and postcards encouraging business owners to purchase advertisements in the guide.

Victor Hugo Green in 1956

Victor Hugo Green in 1956

Most editions of the Green Book contained articles, but these were rather short at the beginning of the guide’s existence; throughout the years, though, the guide integrated more expansive articles, portraying, for example, “cities with large and welcoming black neighborhoods, like Chicago and Louisville, that catered to tourists.” The listings and advertisements, however, remained at the very heart of the Green Book’s mission.

Standard Oil Company became the privileged business partner of Victor Green; indeed, its Esso gas stations sold The Green Book starting in the mid-1940s or offered it as a promotional item to customers. The United States Travel Bureau also endorsed the guide, which gave the book national attention. Other partnerships developed by Green to foster the book’s distribution included several travel clubs and bureaus, automobile clubs, the armed forces, bookstores, bus and airline companies, and the Idlewild Chamber of Commerce – a large African American resort in Michigan.

By the beginning of the 1950s, The Green Book included listings for lodgings in Canada and Mexico, the Caribbean, Costa Rica, Bermuda and the Virgin Islands; later, by the 1960s, the guide included listings for Europe and Africa. Interestingly, while commentators like Gretchen Sorin mention that the Green Book was at first reserved in its tone regarding racial issues, since Green and his team knew that they relied heavily on white allies, corporations and government agencies to ensure the survival of their publication, Sorin also insists on the fact that the Green Books of the 1960s explicitly supported the civil rights movement:

“In a feature entitled "Your Rights, Briefly Speaking," drawn from a list compiled by the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, Green Book writers listed the states that passed laws against any form of discrimination. […] this segment sought to inspire readers to challenge the laws by reporting violations experienced during travel to the appropriate human rights commission. Contact information was included for each of the 20 states with such commissions. The descriptions of the violations encouraged readers to file lawsuits, to seek monetary damages against wrongful actions, and to demonstrate peacefully.”

Other travel guides were created in the attempt to help black drivers overcome some of the difficulties they faced on the road. Other than the Green Book, other guides included Hackley and Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers (1930-1931); The Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring (1952-1959); and Travelguide (1947-1963). The Green Book, however, was the longest lasting – published from 1937 to 1966. It was also the most widely distributed of these guides, reaching a circulation of 2 million in 1962.

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

-Bay, Mia, “Traveling Black/Buying Black. Retail and Roadside Accommodations during the Segregation Era,” in Ann Fabian and Mia Bay (eds.), Race and Retail: Consumption across the Color Line, New Brunswick (N.J.), Rutgers University Press, 2015, p. 15-33.

-Sorin, Gretchen, “Victor and Alma Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book,” in

Driving While Black. African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights, New York, Liveright Publishing Corporation (a division of W. W. Norton & Company), 2020, p. 176-214.

-Sugrue, Thomas J., “Driving While Black: The Car and Race Relations in Modern America.” Automobile in American Life and Society, Science and Technology Studies Program at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and Benson Ford Research Center (The Henry Ford), 2004-2010, http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Race/R_Casestudy/R_Casestudy1.htm

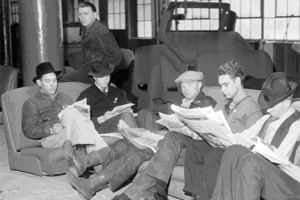

The 1936 Flint Sit-Down strike took the UAW from a collection of isolated locals on the outside of the industry to a major union that led to the unionization of the domestic auto industry...

The 1936 Flint Sit-Down strike took the UAW from a collection of isolated locals on the outside of the industry to a major union that led to the unionization of the domestic auto industry...