In 1902, the City Directory listed three auto companies and one supplier firm. By 1915, listings had exploded to 48 manufacturers and 100 suppliers, and plenty of them were in southwest Detroit.

Detroit became a magnet for mechanics and inventors alike, including Henry Ford and Carl Blomstrom. Blomstrom came to Detroit in 1901 from Marquette after a decade of building marine gas engines. His experiments with automobile engines that began in 1897 led him to patent a two-cylinder engine in 1903. A year later, he acquired a plant on Clark near River Road, not far from his home across from Clark Park. When Blomstrom’s fortunes faded, operations continued at the plant under the management of the DeLuxe Motor Car Company. Within two years, the auto company Everitt-Metzger-Flanders (E-M-F) purchased the plant, and manufacturing continued at that location after E-M-F merged with Studebaker in 1912.

From “Our Michigan Friends - As We See ‘Em” (1905)

From “Our Michigan Friends - As We See ‘Em” (1905)

Auto manufacturers that few remember today, including Paige-Detroit Motor Company, Federal Motor Truck Company, Northway, Saxon Motor Company, Motorcar Company, Bour-Davis, and Van Dyke Motor Car Company, also established plants in Southwest Detroit. Initially, these firms concentrated on luxury vehicles, each handcrafted individually by skilled workers, and the intense competition resulted in a high failure rate. After 1910, however, successful companies followed Ford’s example by standardizing auto designs and some, including General Motors (GM), competed with Ford by producing low-priced vehicles for the mass market.

Most auto companies in this era purchased parts for assembly from a booming supplier industry. Detroit Copper and Brass, located at Clark St. and Jefferson Ave., became Ford’s major supplier of brass engine parts and ornamentation and maintained a workforce of nearly 1,000. Other large supplier firms, like Timken-Detroit Axle, and Kelsey Wheel Company moved their operations to Detroit, specifically southwest Detroit, to be closer to the automakers who were their customers. Southwest Detroit was also honeycombed with smaller suppliers, like Gilmore Motor Manufacturing Company and Federal Screw Works. Tool and die operations like Coleman Tool, Buell Die & Machine, and Star Tool & Die were among the largest of hundreds of small firms that produced and maintained the industry’s specialty machinery.

(1919)Entrepreneurs and businesses in Southwest Detroit also contributed to auto production in other parts of Detroit. The founders of Michigan Car Company, which built freight cars beginning in the 19th century and ultimately became part of American Car & Foundry, led the investment group that moved the Packard Motor Car Company from Warren, Ohio to Detroit’s east side in the early 1900s. The investors included Richard Joy, a vice president of the Detroit Copper and Brass Rolling Mills, and whose brother Henry served as Packard’s president from 1909 to 1926. The Joy brothers were heirs to the Michigan Central Railroad fortune. Truman Newberry, whose father founded the Michigan Car Company, and had served as a Secretary of the Navy and a US Senator was also a major investor in Packard. By 1902, the Newberry firm, Detroit Steel & Spring Works, became Detroit Steel Castings. The firm originally manufactured rail car springs, but by 1915 was producing light castings for Packard trucks that were used by the French and British armies in World War I.

(1919)Entrepreneurs and businesses in Southwest Detroit also contributed to auto production in other parts of Detroit. The founders of Michigan Car Company, which built freight cars beginning in the 19th century and ultimately became part of American Car & Foundry, led the investment group that moved the Packard Motor Car Company from Warren, Ohio to Detroit’s east side in the early 1900s. The investors included Richard Joy, a vice president of the Detroit Copper and Brass Rolling Mills, and whose brother Henry served as Packard’s president from 1909 to 1926. The Joy brothers were heirs to the Michigan Central Railroad fortune. Truman Newberry, whose father founded the Michigan Car Company, and had served as a Secretary of the Navy and a US Senator was also a major investor in Packard. By 1902, the Newberry firm, Detroit Steel & Spring Works, became Detroit Steel Castings. The firm originally manufactured rail car springs, but by 1915 was producing light castings for Packard trucks that were used by the French and British armies in World War I.

By 1917, Detroit auto companies produced one million cars a year. Car assembly companies employed over 90,000 people, while 44,000 more worked for parts suppliers. With the entry of the U.S. into World War I, the federal government’s military conversion program included a luxury tax on cars to limit production for civilians. In response, automakers built or refitted plants to manufacture plane engines, trucks, ambulances, messenger cars, and other military vehicles.

With war’s end, manufacturers converted their factories back to civilian production, and Southwest Detroit was fundamental to the auto industry’s resurgence. General Motors began manufacturing Cadillacs after razing the American Car & Foundry complex on Clark Street just south of Michigan Avenue. The plant had produced munitions during World War I, but GM invested $15 million in the facility to retool it for luxury automobile production, which continued at that site for over sixty years. Fisher Body, a division of GM that was dedicated, as its name suggests, to the production of automobile bodies, purchased an aircraft plant in 1918 at West End and West Fort Streets as well as a nearby facility that had manufactured small munitions during the war. GM wove production at these sites into its companywide operations, producing auto bodies for the Cadillac Clark Street plant and parts for the entire GM system. Henry Leland’s Lincoln Motor Company, at Warren and Livernois, challenged Cadillac, the firm he had once guided to prominence, by launching a luxury vehicle powered by a V-8 engine derived from his company’s production of wartime V12 Liberty aircraft engines. After Leland’s company floundered, Henry Ford bought it in 1922 and Lincoln became the luxury brand of the Ford Motor Co., with production continuing at the Southwest Detroit site until the early 1950s.

Rickenbacker Cabot St. Factory (1920s)

Rickenbacker Cabot St. Factory (1920s)

The postwar years also saw the creation of new auto firms, for example the Rickenbacker Motor Company, which was located on Cabot Street. Auto industry veterans Barney Everitt and Walter Flanders joined forces with former race car driver and World War I flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker to create the company bearing the fighter pilot’s name. Rickenbacker had earned both the French Croix de Guerre and the Congressional Medal of Honor for downing 26 German planes. Rickenbacker Motor Company secured $5 million to launch a luxury vehicle that featured high horsepower, a low center of gravity for comfort, and four-wheel brakes for safety, a feature regarded as unnecessary at the time. Although it was well-designed and attractive, the Rickenbacker automobile might have been too innovative, as the company closed in 1927 after having sold only 34,500 cars. Rickenbacker himself went on to own the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and become president of Eastern Airlines.

As successful or celebrated as these entrepreneurs were, few could rival the international reputation of Henry Ford, whose Model T was an affordable, utilitarian automobile for farmers and the average family. Ford revolutionized factory production by introducing the moving assembly line at his Highland Park Plant and doubling workers’ earnings to $5 a day, a plan he introduced in early 1914. During World War I, Ford developed property in Dearborn, Michigan, abutting Southwest Detroit, to build the Eagle Boat. After the war, Ford’s new industrial complex, called the Rouge Plant, evolved into the most highly integrated industrial facility in the world and employed thousands of Southwest Detroiters. At peak production, the 2000-acre Rouge Complex included two dozen major structures and employed upwards of 80,000 people, including dockworkers who unloaded the coal, sand, and raw materials necessary to produce steel and glass for cars.

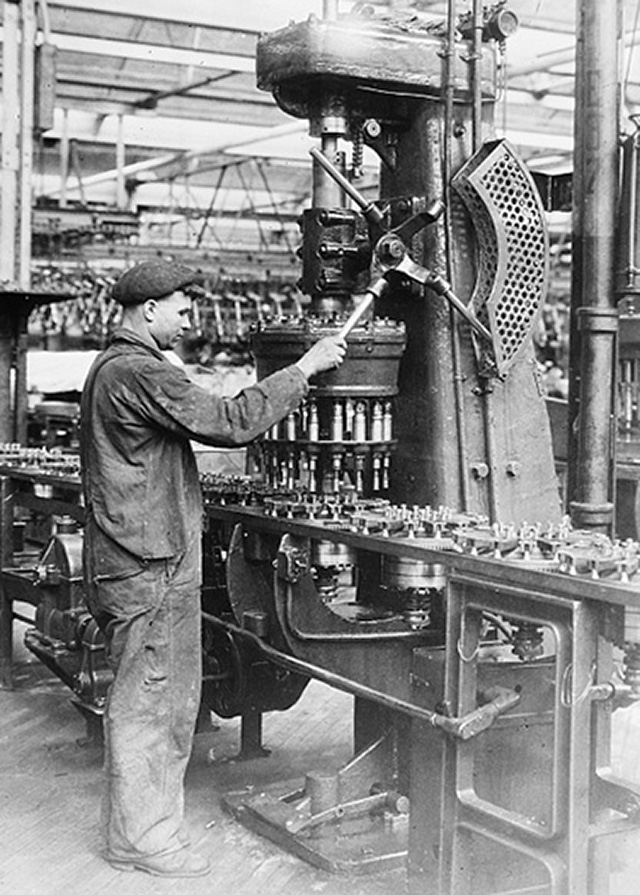

Magnet Screw Setting Operation – Ford Rouge (1919)

Magnet Screw Setting Operation – Ford Rouge (1919)

Auto work attracted job seekers from throughout the United States as well as Canada, Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East. These workers, employed by the tens of thousands to produce parts and assemble autos, often experienced monotonous, grueling conditions on the job. They were employed when market conditions permitted, and the auto industry was notorious for its boom and bust cycles. Many of the workers slept in shifts in cramped apartments before establishing more permanent roots in the community. In these early years, most autoworkers did not own their own cars, relying instead on street trolleys or simply walking to get to work. This was before local governments embraced urban planning principles and zoning ordinances, so Southwest Detroit’s factories and residential neighborhoods were built adjacent to one another and workplaces were likely to be relatively close to living quarters. Similar scenes were common elsewhere in Detroit and in other auto communities like Flint, Michigan, Cleveland, Ohio, and South Bend, Indiana. However, few other cities could match the numbers of factories and autoworkers concentrated in Southwest Detroit, “the neighborhood that built the car.”

Click to view:

Once Teeming with Auto Plants, Detroit Now Home to Only a Few Nameplates, a 2000 Detroit News feature that traces the emergence and consolidation of Detroit auto firms

1923 Rickenbacker Factory Tour, this 22 image slide show posted on the Rickenbacker Club of America website dates from 1923 and highlights production at its original plant (located at 4815 Cabot Avenue)

Labor Routes, an excerpt from Steve Babson’s Working Detroit that traces the paths of those who found their way to Detroit to power the auto industry

Our 19th CENTURY INDUSTRY discussion chronicles Detroit’s prominence as a manufacturer of rail cars. Additional detail about Blomstrom and related firms is found on the CLARK FORT ST. COMPANIES tab. The FIRMS AND SITES post lists other auto companies profiled in the Guide. The WE AUTO KNOW MORE post includes links to other websites that profile other companies of this era.

TEXT & RESEARCH & – RON ALPERN & DIANNE FEELEY

PHOTO CREDITS

Detroit Historical Society

Timken - Detroit Axle / Rickenbacker Cabot St. Factory

Detroit Publishing Company Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Ford Magnet Screw Operation

Library of Congress

Carl Blomstrom Cartoon