The March on Washington occurred in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963, when nearly a quarter-million people assembled on the hill around the Washington Monument and marched to the Lincoln Memorial, where the marchers listened to speeches from the protest’s leaders.

March on Washington picketers image courtesy of The Guardian

March on Washington picketers image courtesy of The Guardian

The march’s objective was to end racial segregation and discrimination in the Jim Crow South, but also to defend the idea – as reflected by the march’s title – that Americans of all racial backgrounds should have the right to access a decent and integrated education, an affordable housing situation, jobs with a living wage, as well as voting rights and access to all stores, restaurants, hotels, etc. Marchers wanted the civil rights bill that President John F. Kennedy had introduced to Congress in June 1963 to pass, but they also thought it should be stronger: they asked for the creation of a “massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers – Negro and white – in meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages,” for the raise of the minimum wage in order to “give all Americans a decent standard of living,” and for many the most essential goal was the establishment of a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to ensure that workers would not be discriminated on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin in labor unions, the private sector, and government agencies.

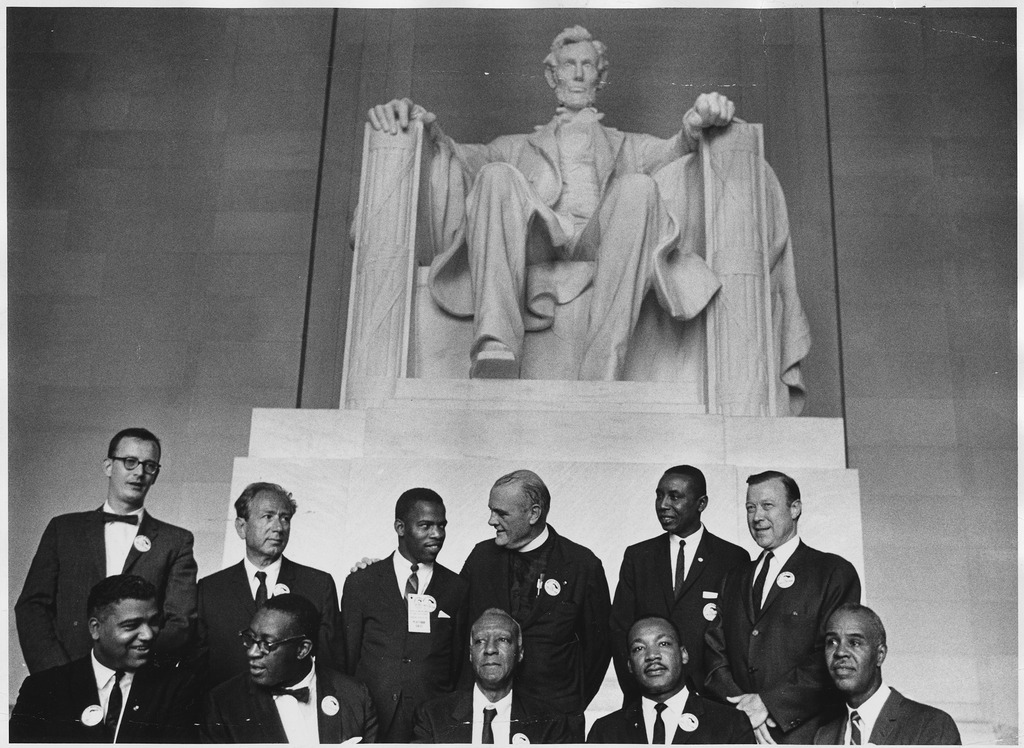

Civil rights and labor leaders at march image courtesy of Library of Congress

Civil rights and labor leaders at march image courtesy of Library of Congress

The initiative for the 1963 March on Washington came from the Negro American Labor Council (NALC) that A. Philip Randolph and African American labor leaders formed to respond to the failure of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) to end racial discrimination in some of its unions. The only woman on the planning committee for the March on Washington, Anna Arnold Hedgeman, was the activist who encouraged the march leaders to include in their demands access to public accommodations and voting rights in the South – which allowed the movement to obtain support from Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), John Lewis’ SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), and James Farmer’s Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Apart from Randolph, King, Lewis and Farmer, the Big Six – the informal name for the leaders of the march – included Roy Wilkins, the executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Whitney Young, the executive director of the National Urban League. Hedgeman also convinced the leaders to reach out to the National Council of Negro Women. Most of the participants in the march had little experience in political demonstrations: “Some were students or full-time activists, but the vast majority consisted of auto workers and meatpackers, teachers and letter carriers, domestic servants and sharecroppers (…)” The march was purposefully made interracial, with white Americans and African Americans walking side by side, in an effort “to be speaking for, as well as to, the nation.”

Martin Luther King’s essential “I have a dream” speech was presented at this march, as the last of ten speeches, ending more than six hours of various presentations and appearances by politicians, but also performances by famous musicians, and declarations of solidarity from various groups -- including some from abroad.

Although cooperation with the Kennedy administration and the ideal of mass-marketing in the organization of the march – reaching as many people as possible through all available means –, produced important compromises in the form and the political demands of the march, including the rejection of the support of radical groups and statements, the legacy of the March on Washington was visible in the Civil Rights Act signed in July 1964 by President Lyndon Johnson: the Civil Rights Act banned employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, and national origin; and, more unexpectedly, banned discrimination based on sex, a result of Anna Hedgeman’s efforts to ensure that the March on Washington movement would reach out to black women’s organizations. The march is not only considered the most famous protest in United States’ history, it has also been referred to in future demonstrations as an explicit model to re-create in 1983, 1993 and 2000, as organizers scheduled their protests for nearly the same day and reintroduced issues related to “Jobs and Freedom” anchored in their own time.

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

-Lucy G. Barber, “In the Great Tradition. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963,” in Marching on Washington. The Forging of an American Political Tradition, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2002, p. 141-178.

- William P. Jones, The March on Washington. Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights, New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, p. x.

- Final Plans for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” unlabeled folder, box 39, BMP. Quoted in William P. Jones, The March on Washington. Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights, New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, p. x.

- Ibid., p. xvii.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. xviii.

- Lucy G. Barber, “In the Great Tradition. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963,” in Marching on Washington. The Forging of an American Political Tradition, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2002, p. 158.

- Ibid., p. 143. Lucy G. Barber writes: “The August 28 march became the first mass-marketed protest in the history of demonstrations in Washington. Skilled organizers and leaders used all available forums – buttons, flyers, newspapers, radio, television, rallies, and concerts – to promote the march and recruit participants.” Ibid., p. 154.

- Ibid., p. 159. Barber also writes that throughout the 1960s, some of the leaders of the march became disillusioned with the event they organized, and that this was due to the compromises necessitated by the ideal of a “mass marketing” of the march. Ibid., p. 178.

- Ibid., p. 141 and p. 173-174.